PART III (B)

Operational Phase of Project Mercury

June 1962 through June 12, 1963

1962

June 13

The Manned Spacecraft Center proposed a recoverable meteoroid experiment. According to the proposal, sheets of aluminium would be extended from the Mercury spacecraft and exposed to a meteoroid environment for a period of about 2 weeks. The sheets would then be retracted into the spacecraft for protection during reentry and recovery.

Memo, John R. Davidson to Langley Associate Director, subject: Recoverable Meteoroid Penetration Experiment Using the Mercury Capsule as a Container, June 19, 1962.

June 25

Scott Carpenter was the fourth individual of Project Mercury to be presented Astronaut Wings by his respective service.

Information supplied by Edwin M. Logan, Astronaut Activities Office, MSC.

June 26

Project Reef, an airdrop program to evaluate the Mercury 63-foot ringsail main parachute's capability to support the higher spacecraft weight for the extended range or 1-day mission was completed. Tests indicated that the parachute qualified to support the mission.

NASA-MSC Report, Project Mercury [Quarterly] Status Report No. 15 for Period Ending July 31, 1962; Monthly Activities Report, Mercury Project Office, July, 1962.

June 27

D. Brainerd Holmes, NASA Director of Manned Space Flight, announced that the Mercury-Atlas 8 (MA-8) manned orbital mission would be programed for as many as six orbits. Walter Schirra was selected as the prime pilot with Gordon Cooper serving as backup.

NASA Historical Office, Aerospace Science and Technology: A Chronology for 1962, June 1962.

NASA's Office of Advanced Research and Technology announced the appointment of Dr. Eugene B. Konecci as Director of Biotechnology and Human Research. Dr. Konecci will be responsible for directing research and development of future life support systems, advanced systems to protect man in the space environment, and research to assure man's performance capability in space.

House Committee, Astronautical and Aeronautical Events of 1962, June 12, 1963.

June 28

The Manned Spacecraft Center requested that the Langley Research Center participate in acoustic tests of ablation materials on Mercury flight tests. Langley was to prepare several material specimens which would be tested for possible application in providing lightweight afterbody heat protection for Apollo class vehicles. Langley reported the results of its test preparation activities on September 21, 1962.

Memo, Langley to Manned Spacecraft Center, subject: Transmittal of Data from Intense Noise Tests of Ablation Materials, Sept. 21, 1962.

June 29

Engineering was completed for the spacecraft reaction control system reserve fuel tank and related hardware in support of the Mercury extended range or 1-day mission.

NASA-MSC Report, Project Mercury [Quarterly] Status Report No. 15 for Period Ending July 31, 1962.

June 30

Personnel strength of the Manned Spacecraft Center was 1,802.

Statistics supplied by Katheryn Walker, Personnel Division, MSC.

July 1

Relocation of the Manned Spacecraft Center from Langley Field to Houston, Texas, was completed.

MSC Fact Sheet No. 59, subject: NASA Manned Spacecraft Center Completes its Relocation to Temporary Houston Facilities, July 1, 1962.

July 8

Controversial Operation Dominic succeeded, after two previous attempts in June, in exploding a megaton-plus hydrogen device at more than 200-mile altitude over Johnston Island in the Pacific. Carried aloft by a Thor rocket and synchronized with the approach of a TRAAC satellite, this highest thermonuclear blast ever achieved was designed to test the influence of such an explosion on the Van Allen radiation belts. The sky above the Pacific Ocean from Wake Island to New Zealand was illuminated by the blast. Later observations by probes and satellites showed another artificial radiation belt to have been created by this series of nuclear tests.

House Committee, Astronautical and Aeronautical Events of 1962, June 12, 1963.

July 9

NASA scientists concluded that the layer of haze reported by astronauts Glenn and Carpenter was a phenomenon called "airglow." Using a photometer, Carpenter was able to measure the layer as being 2 degrees wide. Airglow accounts for much of the illumination in the night sky.

NASA Historical Office, Aerospace Science and Technology: A Chronology for 1962, July 1962.

July 11

NASA officials announced the basic decision for the manned lunar exploration program that Project Apollo shall proceed using the lunar orbit rendezvous as the prime mission mode. Based on more than a year of intensive study, this decision for the lunar orbit rendezvous (LOR), rather than for the alternative direct ascent or earth orbit rendezvous modes, enables immediate planning, research and development, procurement, and testing programs for the next phase of space exploration to proceed on a firm basis. (See 16 June 1961.)

House Committee, Astronautical and Aeronautical Events of 1962, June 12, 1963.

July 13

Tests were conducted with a subject wearing a Mercury pressure suit in a modified Mercury spacecraft couch equipped with a B-70 (Valkyrie) harness. When this harness appeared to offer advantages over the existing Mercury harness, plans were made for further evaluation in spacecraft tests.

MSC Life Systems Division, Weekly Activity Report, July 9-13, 1962.

July 21

President John F. Kennedy announced that Robert R. Gilruth, Director of Manned Spacecraft Center, would receive the President's Award for Distinguished Federal Civilian Service. This award was made for his successful accomplishment of "one of the most complex tasks ever presented to man in this country. . . the achievement of manned flight in orbit around the earth."

NASA Historical Office, Aerospace Science and Technology: A Chronology for 1962, July 1962.

July 27

Atlas launch vehicle No. 113-D was inspected at Convair and accepted for the Mercury-Atlas 8 (MA-8) manned orbital mission.

NASA-MSC Report, Project Mercury [Quarterly] Status Report No. 15 for Period Ending July 31, 1962.

August 6

The Friendship 7 spacecraft of the Mercury-Atlas 6 (MA-6) manned orbital mission (Glenn flight) was placed on display at the Century 21 Exhibition in Seattle, Washington. After this exhibition, the spacecraft was presented to the National Air Museum of the Smithsonian Institution, at formal presentation exercises on February 20, 1963.

Information by Robert Gordon, Exhibits and Displays, Public Affairs Office, MSC.

August 8

Spacecraft 9 (redesignated 9A) was phased into the Project Orbit program in preparation for the Mercury extended range or 1-day mission.

Actual testing began in September 1962. NASA-MSC Report, Project Mercury [Quarterly] Status Report No. 15 for Period Ending July 31, 1962.

Atlas launch vehicle 113-D was delivered to Cape Canaveral for the Mercury-Atlas 8 (MA-8) manned orbital mission.

Data supplied by Ken Vogel, Mercury Project Office, MSC.

August 10

NASA announced the appointment of Dr. Robert L. Barre as Scientist for Social, Economic, and Political Studies in the Office of Plans and Program Evaluation. Dr. Barre will be responsible for developing NASA's program of understanding, interpreting, and evaluating the social, economic, and political implications of NASA's long-range plans and accomplishments.

House Committee, Astronautical and Aeronautical Events of 1962, June 12, 1963.

August 11

A spacecraft reaction control system test was completed. Data compiled from this test was used to evaluate the thermal and thruster configuration of the Mercury extended range or 1-day mission spacecraft.

NASA-MSC Report, Project Mercury [Quarterly] Status Report No. 16 for Period Ending October 31, 1962.

August 11-12

U.S.S.R. launched VOSTOK III into orbit, piloted by Major Andrian G. Nikolayev. The next day, August 12, VOSTOK IV was launched into orbit piloted by Lt. Colonel Pavel R. Popovich, and near-rendezvous was achieved.

House Committee, Astronautical and Aeronautical Events of 1962, June 12, 1963.

August 15/

Navy swimmers, designated for the Mercury-Atlas 8 (MA-8) manned orbital mission recovery area, started refresher training at Pensacola, Florida. Instruction included installing the auxiliary flotation collar on a boilerplate spacecraft and briefings on assisting astronaut egress from the spacecraft.

NASA-MSC Report, Project Mercury [Quarterly] Status Report No. 15 for Period Ending July 31, 1962.

August 21

A conference was held at the Rice Hotel, Houston, Texas, on the technical aspects of the Mercury-Atlas 7 (MA-7) manned orbital mission (Carpenter flight).

Conference attended by author.

August (during the month)

The first edition of the map for the Mercury 1-day mission was published.

USAF Aeronautical Chart and Information Center, 1st ed., Aug. 1962.

August-September

Negotiations were completed with McDonnell for spacecraft configuration changes to support the Mercury 1-day manned orbital mission. The design engineering inspection, when the necessary modifications were listed, was held on June 7, 1962.

NASA-MSC Report, Project Mercury [Quarterly] Status Report No. 15 for Period Ending July 31, 1962.

September 7

The results of a joint study by the Atomic Energy Commission, the Department of Defense, and NASA concerning the possible harmful effects of the artificial radiation belt created by Operation Dominic on Project Mercury's flight MA-8 were announced. The study predicted that radiation on outside of capsule during astronaut Walter M. Schirra's six-orbit flight would be about 500 roentgens but that shielding, vehicle structures, and flight suit would reduce this dosage down to about 8 roentgens on the astronaut's skin. This exposure, well below the tolerance limits previously established, would not necessitate any change of plans for the MA-8 flight.

House Committee, Astronautical and Aeronautical Events of 1962, June 12, 1963.

September 8

Atlas launch vehicle 113-D for the Mercury-Atlas 8 (MA-8) manned orbital mission was static-fired at Cape Canaveral. This test was conducted to check modifications that had been made to the booster for the purpose of smoother engine combustion.

Mercury Project Office, Monthly Activity Report, Sept. 1962.

September 10

The Mercury-Atlas 8 (MA-8) manned orbital mission was postponed and rescheduled for September 28, 1962, to allow additional time for flight preparation.

NASA Historical Office, Aerospace Science and Technology: A Chronology for 1962, Sept. 1962.

September 12

President John F. Kennedy visited the Manned Spacecraft Center and was shown exhibits including Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo spacecraft hardware.

MSC Weekly Activity Report for the Office of the Director of Manned Space Flight, Sept. 2-8, 1962.

NASA announced it would launch a special satellite before the end of the year "to obtain information on possible effects of radiation on future satellites and to give the world's scientific community additional data on the artificial environment created by the radiation belt." The 100-pound satellite would be launched from Cape Canaveral into an elliptical orbit ranging from about 170-mile perigee to 10,350-mile apogee.

First "mystery" satellite in history of space exploration was launched, according to British magazine Flight International. The magazine said the satellite orbited at a height of 113 miles and reentered the earth's atmosphere 12 days later. The satellite was listed as belonging to the U.S. Air Force, but spokesman said this was a "scientific guess based on our assessment of previous satellite launchings." Launching was not confirmed, and no official U.S. listing included such a satellite.

House Committee, Astronautical and Aeronautical Events of 1962, June 12, 1963.

September 17

Studies completed by the Navy Biophysics Branch of the Navy School of Aviation Medicine, Pensacola, Florida, disclosed that astronaut Glenn had received less than one-half the cosmic radiation dosage expected during his orbital flight. The Mercury-Atlas 6 (MA-6) spacecraft walls had served as excellent protection.

NASA Historical Office, Aerospace Science and Technology: A Chronology for 1962, Sept. 1962.

September 18

Donald Slayton, one of the seven chosen for the astronaut training program, was designated Coordinator of Astronaut Activities at the Manned Spacecraft Center.

Robert R. Gilruth, MSC Announcement No. 87 2-2, subject: Coordinator of Astronaut Activities, Sept. 18, 1962.

The NASA spacecraft test conductor and the Convair test conductor notified the interface committee chairman of the readiness-for-mate of the adapter-interface area of the Mercury-Atlas 8 (MA-8).

Memo, O. L. Duggan to Associate Director, MSC, subject: MA-8 (Spacecraft 16) Interface Inspection, Sept. 18, 1962.

September 22

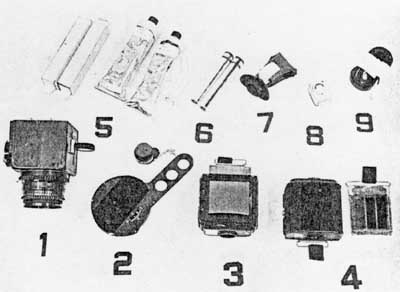

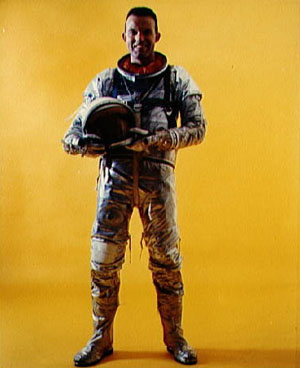

As an experiment, Walter Schirra planned to carry a special 2.5-pound hand camera aboard the Mercury-Atlas 8 (MA-8) spacecraft. (See fig. 64.) During the flight, the astronaut would attempt to arrive at techniques that could be applied to an advanced Nimbus weather satellite.

NASA-MSC Report, Project Mercury [Quarterly] Status Report No. 16 for Period Ending October 31, 1962.

|

|

Figure 64. MA-8 ditty bag contents: 1. Camera (see text), 2. Photometer, 3. Color film magazine, 4. Film magazine, 5. Food containers, 6. Dosimeter, 7. Motion sickness container, 8. Exposure meter, 9. Camera shoulder strap.

|

September 28

Walter Schirra made a 6.5 hour simulated flight in the Mercury-Atlas 8 (MA-8) spacecraft. The worldwide tracking network of 21 ground stations and ships also participated in the exercise.

NASA-MSC Report, Project Mercury [Quarterly] Status Report No. 16 for Period Ending October 31, 1962.

October 1

Tropical storm "Daisy" was studied by Mercury operations activities for its possible effects on the Mercury-Atlas 8 (MA-8) mission, but flight preparations continued.

NASA Historical Office, Aerospace Science and Technology: A Chronology for 1962, Oct. 1962.

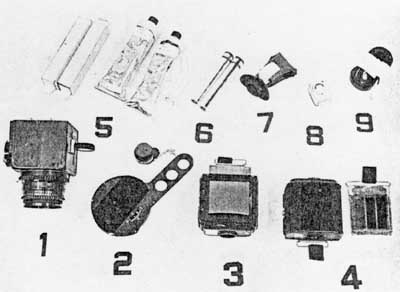

October 3

Mercury-Atlas 8 (MA-8), designated Sigma 7, was launched from Cape Canaveral with astronaut Walter Schirra as the pilot for a scheduled six-orbit flight. (See fig. 65.) Two major modifications had been made to the spacecraft to eliminate difficulties that had occurred during the Glenn and Carpenter flights. The reaction control system was modified to disarm the high-thrust jets and allow the use of low-thrust jets only in the manual operational mode to conserve fuel. A second modification involved the addition of two high frequency antennas mounted onto the retro package to assist and maintain spacecraft and ground communication throughout this flight. Schirra termed his six-orbit mission a "textbook flight." About the only difficulty experienced was attaining the correct pressure suit temperature adjustment. The astronaut became quite warm during the early orbits, but at a subsequent press conference he reported there had been many days at Cape Canaveral when he had been much hotter sitting under a tent on the beach. To study fuel conservation methods, a considerable amount of drifting was programed during the MA-8 mission. This included 118 minutes during the fourth and fifth orbits and 18 minutes during the third orbit. Since drift error was slight, attitude fuel consumption was no problem. At the start of the reentry operation there was a 78 percent supply in both the automatic and manual tanks, enabling Schirra to use the automatic mode during reentry. After a 9 hour and 13 minute orbital flight, the MA-8 landed 275 miles northeast of Midway Island, 9,000 yards from the prime recovery ship, the USS Kearsarge. Schirra stated that he and the spacecraft could have continued for much longer. The flight was the most successful to that time. Besides the camera experiment (September 22, 1962, entry), nine ablative material samples were laminated onto the cylindrical neck of the spacecraft, and radiation-sensitive emulsion packs were placed on each side of the astronaut's couch. As a note of unusual interest, the MA-8 launch was relayed via the Telstar satellite to television audiences in Western Europe.

NASA, Results of the Third United States Manned Orbital Space Flight, October 3, 1962, SP-12.

|

|

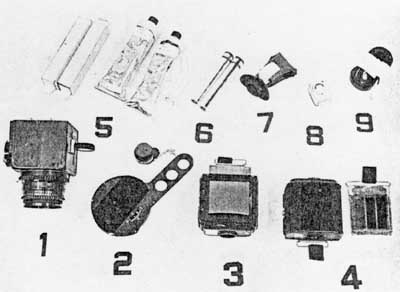

Figure 65. Astronaut departs transfer van for Mercury-Atlas gantry.

|

October 5

Spacecraft 16, Sigma 7, was returned to Hanger S at Cape Canaveral for postflight work and inspection. It was planned to retain the Sigma 7 at Cape Canaveral for permanent display.

NASA-MSC Report, Project Mercury [Quarterly] Status Report No. 16 for Period Ending October 31, 1962; Data supplied by Ken Vogel, Mercury Project Office, MSC; Message MSC-74 NASA-MSC-AMR Operations to Robert R. Gilruth, MSC, Oct. 29, 1962.

Dr. Charles A. Berry, Chief of Aerospace Medical Operations, Manned Spacecraft Center, reported that preliminary dosimeter readings indicated that astronaut Schirra had received a much smaller radiation dosage than expected.

NASA Historical Office, Aerospace Science and Technology: A Chronology for 1962, Oct. 1962.

A U.S. Air Force spokesman, Lt. Colonel Albert C. Trakowski, announced that special instruments on unidentified military test satellites had confirmed the danger that astronaut Walter M. Schirra, Jr., could have been killed if his MA-8 space flight had taken him above a 400-mile altitude. The artificial radiation belt, created by the U.S. high altitude nuclear test in July, sharply increases in density above 400-miles altitude at the geomagnetic equator and reaches peak intensities of 100 to 1,000 times normal levels at altitudes above 1,000 miles.

House Committee, Astronautical and Aeronautical Events of 1962, June 12, 1963.

October 7

The Mercury-Atlas 8 (MA-8) press conference was held at the Rice University, Houston, Texas. Astronaut Schirra expressed his belief that the spacecraft was ready for the 1-day mission, that he experienced absolutely no difficulties with his better than 9 hours of weightlessness, and that the flight was of the "textbook" variety.

Transcript of Press Conference (MA-8) held at Rice University, Oct. 8, 1962.

October 9

Spacecraft 20 was delivered to Cape Canaveral for the Mercury-Atlas 9 (MA-9) 1-day mission flight.

Data supplied by Ken Vogel, Mercury Project Office, MSC.

October 15

A high frequency direction finding system study was initiated. This study, covering a 12-month period, involved the development of high-frequency direction finding techniques to be applied in a network for locating spacecraft. The program was divided into a 5-month study and feasibility phase, followed by a 7-month program to provide operational tests of the procedures during actual Mercury flights or follow-on operations.

Letter, Kellogg Space Communications Laboratory to MSC, subject: Contract No. NAS 9-804, Oct. 22, 1962.

Walter Schirra was awarded the NASA Distinguished Service Medal by James Webb, NASA Administrator, for his six-orbit Mercury-Atlas 8 (MA-8) flight in a ceremony at his hometown, Oradell, New Jersey.

Information supplied by Ivan Ertel, Publi Affairs Office, MSC.

October 16

Walter Schirra became the fifth member of the Project Mercury team to receive Astronaut Wings.

Information supplied by Ivan Ertel, Publi Affairs Office, MSC.

October 19

McDonnell reported that all spacecraft system tests had been completed for spaceraft 20, which was allocated for the Mercury-Atlas 9 (MA-9) 1-day orbital mission.

McDonnell Report, subject: Model 133L- Project Mercury Spacecraft No. 20 Capsule Systems Tests, Oct. 19, 1962.

October 23

Major General Leighton Davis, Department of Defense representative for Project Mercury Support Operations, reported that support operation planning was underway for the Mercury 1-day mission.

Letter, Air Force Missile Test Center to Robert S. McNamara, Secretary of Defense, subject: Department of Defense Support of Mercury-Atlas (MA-8), Oct. 23, 1962, with inclosures.

The Air Force Missile Test Center, Cape Canaveral, Florida, submitted a report to the Secretary of Defense summarizing Department of Defense support during the Mercury-Atlas 8 (MA-8) six-orbit flight mission.

Letter, Air Force Missile Test Center to Robert S. McNamara, Secretary of Defense, subject: Department of Defense Support of Mercury-Atlas (MA-8), Oct. 23, 1962, with inclosures.

October 25

NASA Associate Administrator Robert C. Seamans, Jr., presented Outstanding Leadership Awards to Maxime A. Faget, Assistant Director for Engineering and Development, Manned Spacecraft Center, and George B. Graves, Jr., Assistant Director for Information and Control Systems. Also, at the NASA annual awards ceremony the Administrator, James E. Webb, presented Group Achievement Awards to four Manned Spacecraft Center activities: Assistant Directorate for Engineering and Development, Preflight Operations Division, Mercury Project Office, and Flight Operations Division.

NASA Historical Office, Aerospace Science and Technology: A Chronology for 1962, Oct. 1962.

October 30

NASA announced realignment of functions within the office of Associate Administrator Robert C. Seamans, Jr. D. Brainerd Holmes assumed new duties as a Deputy Associate Administrator of Manned Space Flight. NASA field installations engaged primarily in manned space flight (Marshall Space Flight Center, MSC, and Launch Operations Center) would report to Holmes; installations engaged principally in other projects (Ames, Lewis Research Center, Langley Research Center, Goddard Space Flight Center, Jet Propulsion Laboratory, and Wallops Island) would report to Thomas F. Dixon, Deputy Associate Administrator for the past year. Previously, most field center directors had reported directly to Dr. Seamans on institutional matters beyond program and contractural administration.

House Committee, Astronautical and Aeronautical Events of 1962, June 12, 1963.

November 1

Mercury Procedures Trainer No. 1, redesignated Mercury Simulator, was moved from Langley Field on July 23, 1962, and installed and readied for operations in a Manned Spacecraft Center building at Ellington Air Force Base, Houston, Texas.

Activity Report, Flight Crew Operations Division, MSC, Aug. 20-28, 1962.

November 4

Enos, the 6-year-old chimpanzee who made a two-orbit flight around the earth aboard the Mercury-Atlas 5 (MA-5) spacecraft (November 29, 1961, entry) died at Holloman Air Force Base, New Mexico. The chimpanzee had been under night and day observation and treatment for 2 months before his death. He was afflicted with shigella dysentary, a type resistant to antibiotics, and this caused his death. Officials at the Air Medical Research Laboratory stated that his illness and death were in no way related to his orbital flight the year before.

Information supplied by Aeromedical Research Center, Albuquerque, New Mexico, Nov. 6, 1962.

November 13

Gordon Cooper was named as the pilot for Mercury-Atlas 9 (MA-9) 1-day orbital mission slated for April 1963. Alan Shepard, pilot of Mercury-Redstone 3 (MR-3) was designated as backup pilot.

NASA Hq. Release No. 52-245, subject: Cooper Named Pilot for MA-9 Flight, Nov. 14, 1962.

The B. F. Goodrich Company reported that it had successfully designed, fabricated, and tested a pivoted light attenuation tinted visor to be mounted on a government-issued Mercury helmet.

Technical Report No. 62E-006, subject: Pivoted Light Attenuation Tinted Visor Helmet, submitted by B. F. Goodrich, Aerospace and Defense Products to MSC, Nov. 13, 1962.

November 16

The Manned Spacecraft Center presented the Department of Defense with recovery and network support requirements for Mercury-Atlas 9 (MA-9) 1-day manned orbital mission.

Letter, MSC to Air Force Missile Test Center, subject: Project Mercury Preliminary Recovery and Network Requirements for MA-9, Nov. 16, 1962.

Mercury spacecraft 15A was delivered to Cape Canaveral for the Mercury-Atlas 10 (MA-10) orbital manned 1-day mission.

Data supplied by Ken Vogel, Mercury Project Office, MSC (See also August 13, 1961, entry).

November 28

Mercury Simulator 2 was modified to the 1-day Mercury orbital configuration in preparation for the Mercury-Atlas 9 (MA-9) flight.

Memo, Riley D. McCafferty to Mercury Project Office, subject: Mercury Flight Simulator Status Report, Nov. 28, 1962.

On this date, the McDonnell Aircraft Corporation reported that as of October 31, 1962, it had expended 4,231,021 man-hours in engineering; 478,926 man-hours in tooling; and 2,509,830 man-hours in production in support of Project Mercury.

Letter, McDonnell to MSC, subject: Contract NAS 5-59, Mercury, Monthly Financial Report, Nov. 28, 1962.

Retrofire was reported to have initiated 2 seconds late during the Mercury-Atlas 8 (MA-8) mission. Because of this, the mechanics and tolerances of the Mercury orbital timing device were reviewed for the benefit of operational personnel, and the procedural sequence for Mercury retrofire initiation was outlined.

Memo, J. D. Collier to John Hodge, Flight Operations Division, subject: Mercury Retrofire Initiation by the Spacecraft Satellite Clock, Nov. 28, 1962.

December 3-4

A pre-operational conference for the Mercury-Atlas 9 (MA-9) 1-day mission was held at Patrick Air Force Base, Florida, to review plans and the readiness status of the Department of Defense to support the flight. Operational experiences during the six-orbit Mercury-Atlas 8 (MA-8) mission were used as a planning guideline.

Letter, Air Force Missile Test Center to MSC, et al., subject: Minutes of Pre-Operational Conference for Project Mercury One-Day Mission (MA-9), Dec. 18, 1962.

December 4

Information was received from the NASA Inventions and Contributions activity that seven individuals, a majority of whom were still associated with the Manned Spacecraft Center, would receive monetary awards for inventions that were important in the development of Project Mercury. These were: Andre Meyer ($1,000) for the vehicle parachute and equipment jettison equipment; Maxime Faget and Andre Meyer (divided $1,500) for the emergency ejection device; Maxime Faget, William Bland, and Jack Heberlig (divided $2,000) for the survival couch; and Maxime Faget, Andre Meyer, Robert Chilton, Williard Blanchard, Alan Kehlet, Jerome Hammack, and Caldwell Johnson (divided $4,200) for the spacecraft design. Formal presentation of these awards was made on December 10, 1962.

Letter, James A. Hootman, NASA Hq. to Dr. Robert R. Gilruth, MSC, subject: Monetary Awards for Project Mercury Inventors, Dec. 4, 1962.

December 7

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology Instrumentation Laboratory, charged with the development of the Apollo guidance and navigation system, was in the process of studying the earth's sunset limb to determine if it could be used as a reference for making observations during the mid-course phase of the mission. To obtain data for this study, the laboratory requested that photographic observations be made during the Mercury-Atlas 9 (MA-9) 1-day orbital mission. Photographic material from the Mercury-Atlas 7 (MA-7 - Carpenter flight) had been used in this study.

Letter, Massachusetts Institute of Technology to MSC, Dec. 7, 1962.

December 14

Notice was received by the Manned Spacecraft Center from the NASA Office of International Programs that diplomatic clearance had been obtained for a survey trip to be conducted at the Changi Air Field, Singapore, in conjunction with Project Mercury contingency recovery operations. Also, the United Kingdom indicated informally that its protectorate, Aden, could be used for contingency recovery aircraft for the Mercury-Atlas 9 (MA-9) 1-day mission.

Memo, Carl N. Jones, NASA Hq. to Christopher C. Kraft, MSC, subject: Use of Aden and Singapore for Contingency Recovery Purposes, Dec. 14, 1962.

December 15

Facilities at Woomera, Australia, a segment of the Mercury global network for telemetry reception and air-to-ground voice communications, was declared no longer required for Mercury flights.

Memo, George M. Low to NASA Director of Network Operations and Facilities, subject: Fixture Requirements for Woomera Telemetry and Air-to-Ground Facilities, Dec. 15, 1962.

December 31

After reviewing Mercury-Atlas 9 (MA-9) recovery and network support requirements, the document covering the Department of Defense support of Project Mercury was forwarded to appropriate Department of Defense operational units for indication of their capability to fulfill requirements.

Letter, Air Force Missile Test Center Hq. to COMDESFLOTFOUR, et al., subject: Department of Defense Support of Project Mercury Operations (MA-9), Dec. 31, 1962.

As of this date, the cumulative cost of the Mercury spacecraft design and development program with the McDonnell Aircraft Corporation, Contract NAS 5-59, had reached $135,764,042. During the tenure of this contract, thusfar, there had been 56 amendments and approximately 379 contract change proposals (CCP). At the end of the year, McDonnell had about 325 personnel in direct labor support of Project Mercury. Between March and May of 1960, the personnel complement had been slightly better than 1,600, representing a considerable rise from the 50 people McDonnell had assigned in January 1959 when study and contract negotiations were in progress. Peak assignments by month and by activity were as follows: Tooling - February 1960; Engineering - April 1960; and Production - June 1960.

Letter, McDonnell to MSC, subject: Contract NAS 5-59, Mercury, Monthly Financial Report, Jan. 25, 1962, with inclosures.

December (during the month)

Three categories of experiments were proposed for the Mercury-Atlas 9 (MA-9) manned orbital mission: (1) space flight engineering and operations, (2) biomedical experiments, and (3) space science. The trailing balloon, similar to the MA-7 (Carpenter flight), was to be included. This balloon would be ejected, inflated, trailed, and jettisoned while in orbit. Another experiment was the installation of a self-contained flashing beacon installed on the retropackage, which would be initiated and ejected from the retropackage during orbital flight. And a geiger counter experiment was planned to determine radiation levels at varying orbital altitudes.

Memo, Eugene M. Shoemaker, Chairman, Manned Space Science Planning Group to Director, Office of Manned Space Flight, Dec. 1962.

1963

January 3

Tentative plans were made by NASA to extend the Mercury-Atlas 9 (MA-9) flight from 18 to 22 orbits.

NASA Historical Office, Astronautics and Aeronautics Chronology of Science and Technology in the Exploration of Space, January 1963.

January 7

Final acceptance tests were conducted on the Mercury space flight simulator at Ellington Field, Texas. This equipment, formerly known as the procedures trainer, was originally installed at Langley Field and was moved from that area to Houston. Personnel of the Manned Spacecraft Center and the Farrand Optical Company conducted the acceptance tests.

Letter, Farrand Optical Company, Inc., to NASA MSC, subject: Progress Report, Space Flight Simulator for Mercury Capsule, Jan. 22, 1963, with inclosures.

January 10-16

During this period, Mercury spacecraft No. 9A was cycled through Project Orbit Mission Runs 108, 108A, and 108B in the test facilities of the McDonnell Aircraft Corporation. These runs were scheduled for full-scale missions and proposed to demonstrate a 1-day mission capability. In otherwords, plans called for the operation of spacecraft systems according to the MA-9 flight plan, including the use of onboard supplies of electrical power, oxygen, coolant water, and hydrogen peroxide. Hardlines were used to simulate the astronaut control functions. Runs 108A and 108B were necessitated by an attempt to achieve the prescribed mission as cabin pressure difficulties forced a halt to the reaction control system thrust chamber operations portion of Run 108, although the other systems began to operate as programed. Later in 108 difficulties developed in the liquid nitrogen flow and leaks were suspected. Because of these thermal simulation problems, the test was stopped after 1 hour. Little improvement was recorded in Run 108A as leaks developed in the oxygen servicing line. In addition, cabin pressures were reduced to one psia, and attempts to repressurize were unsuccessful. The run was terminated. Despite the fact that Run 108B met with numerous problems - cabin pressure and suit temperature - a 40-hour and 30-minute test was completed.

Letter, McDonnell Aircraft Corporation to NASA MSC, subject: Project Mercury, Model 133L, Project Orbit Spacecraft No. 9A T+ 3 Day Test Report, Category IV-I, Runs 108, 108A, 108B, Transmittal of, Jan. 25, 1963.

January 11

The Project Engineering Field Office (located at Cape Canaveral) of the Mercury Project Office reported on the number of changes made to spacecraft 20 (MA-9) as of that date after its receipt at Cape Canaveral from McDonnell in St. Louis. There were 17 specific changes, which follow: one to the reaction control system, one to the environmental control system, seven to the electrical and sequential systems, and eight to the console panels.

Report, subject: Differences between Spacecraft 16 (MA-8) and Spacecraft 20 (MA-9) as of January 11, 1963, with Chart, subject: Summary of Spacecraft 20 Changes.

January 14

Mercury spacecraft 15A was redesignated 15B and allocated as a backup for the MA-9 mission. In the event Mercury-Atlas 10 (MA-10) were flown, 15B would be the prime spacecraft. Modifications were started immediately with respect to the hand controller rigging procedures, pitch and yaw control valves, and other technical changes.

Memo, Wilbur Allaback to Kenneth Vogel, Engineering Operations, Mercury Project Office, subject: Project Mercury Spacecraft, Jan. 31, 1963.

The Manned Spacecraft Center presented the proposal to NASA Headquarters that the ground light visibility experiment of the Schirra flight (MA-8) be repeated for the Mercury-Atlas 9 (MA-9) mission. Objectives were to determine the capability of an astronaut visually to aquire a ground light of known intensity while in orbit and to evaluate the visibility of the light as seen from the spacecraft at varying distances from the light source. Possibly at some later date such lights could be used as a signal to provide spacecraft of advanced programs with an earth reference point. This experiment was integrated as a part of the MA-9 mission.

Memo, Flight Control Operations Division to Mercury Project Manager, subject: Ground Light Visibility Experiment, Jan. 14, 1963.

January 17

Asked by a Congressional committee if NASA planned another Mercury flight after MA-9, Dr. Robert C. Seamans stated, in effect, that schedules for the original Mercury program and the 1-day orbital effort were presumed to be completed in fiscal year 1963. If sufficient test data were not accumulated in the MA-9 flight, backup launch vehicles and spacecraft were available to fulfill requirements.

NASA Historical Office, Astronautics and Aeronautics Chronology, January 1963.

January 21

After reviewing the MA-9 spacecraft system and mission rules, the Simulations Section reported the drafting of a simulator training plan for the flight. Approximately 20 launch reentry missions were scheduled, plus variations of these missions as necessary. Instruction during the simulated orbital period consisted of attitude and fuel consumption studies, and from time to time fault insertions would be integrated to provide a complete range of activities covering all mission objectives. By the end of April 1963, the pilot and backup pilot had accumulated 50 hours in the simulators.

Memo, Simulation Operations Section to Assistant Chief for Training, subject: MA-9 Astronaut Training, Jan. 21, 1963; NASA-MSC Report, Project Mercury (MODM Project) [Quarterly] Status Report No. 18 for Period Ending April 30, 1963.

January 22

McDonnell Aircraft Corporation reported to the Manned Spacecraft Center on a study conducted to ascertain temperature effects on the spacecraft as a result of white paint patch experiments. On both the MA-7 and MA-8 spacecraft, a 6-inch by 6-inch white patch was painted to compare shingle temperatures with an oxidized surface; the basic objective was to obtain a differential temperature measurement between the two surfaces, which were about 6 inches apart. Differences in spacecraft structural points prevented the tests from being conclusive, but the recorded temperatures during the flights were different enough to determine that the painted surfaces were cooler at points directly beneath the patch and on a corresponding point inside the spacecraft. According to McDonnell's analytical calculations, white painted spacecraft were advantageous for extended-range missions. However, McDonnell pointed out the necessity for further study, since one limited test was not conclusive.

Letter, McDonnell Aircraft to NASA-MSC, subject: Contract NAS 5-59, Project Mercury, Models 133K and L, Results of McDonnell MMS-450 Type II White Paint on MA-7 and MA-8 Flights, Jan. 22, 1963.

January 26

Specialty assignments were announced by the Manned Spacecraft Center for its astronaut team: L. Gordon Cooper, Alan B. Shepard, pilot phases of Project Mercury; Virgil I. Grissom, Project Gemini; John H. Glenn, Project Apollo; M. Scott Carpenter, lunar excursion training; Walter M. Schirra, Gemini and Apollo operations and training; Donald K. Slayton, remained in duties assigned in September 1962 as Coordinator of Astronaut Activities. These assignments superseded those of July 1959. Assignments of the new flight-crew members selected on September 17, 1962, were as follows: Neil A. Armstrong, trainers and simulators; Frank Borman, boosters; Charles Conrad, cockpit layout and systems integration; James A. Lovell, recovery systems; James A. McDivitt, guidance and navigation; Elliott M. See, electrical, sequential, and mission planning; Thomas P. Stafford, communications, instrumentation, and range integration; Edward H. White, flight control systems; John W. Young, environmental control systems, personal and survival equipment.

MSC Release 63-11, Jan. 26, 1963.

January 27

John A. Powers, Public Affairs Officer, Manned Spacecraft Center, told an audience of Texas Associated Press managing editors that Gordon Cooper's MA-9 flight might go as many as 22 orbits, lasting 34 hours.

Associated Press Release, Jan. 28, 1963.

February 1

Kenneth S. Kleinknecht, Manager, Mercury Project Office, reported the cancellation of a peroxide expulsion experiment previously planned for the MA-9 mission. Kleinknecht noted the zodiacal light experiment would proceed and that the astronaut's gloves were being modified to facilitate camera operation.

MSC Staff Meeting, Feb. 1, 1963.

February 5

Manned Spacecraft Center officials announced a delay of the MA-9 scheduled flight data due to electrical wiring problems in the Atlas launch vehicle control system.

MSC Release 63-20, Feb. 5, 1963.

February 5-14

Personnel of the Manned Spacecraft Center visited the McDonnell plant in St. Louis to conduct a spacecraft status review. Units being inspected were spacecrafts 15B and 20. In addition, the status of the Gemini Simulator Instructor Console was assessed. With regard to the spacecraft inspection portion, a number of modifications had been made that would affect the simulator trainers. On spacecraft 15B, 15 modifications were made to the control panel and interior, including the relocation of the water separator lights, the addition of water spray and radiation experiment switches and a retropack battery switch. The exterior of the spacecraft underwent changes as well, involving such modifications as electrical connections and redesign of the fuel system for the longer mission. The reviewers found that spacecraft 20 conformed closely to the existing simulator configuration, so that modifications to the simulator were unnecessary.

Memo, Simulator Operations Section to Assistant Chief for Training, subject: Mercury Spacecraft Status Review, March 5, 1963.

February 7

At a Development Engineering Inspection for the spacecraft 15B mockup, designated for the MA-10 mission, some 42 requests for alterations were listed.

NASA-MSC Report, Project Mercury (MODM Project) [Quarterly] Status Report No. 18 for Period Ending April 30, 1963.

February 12

Objectives of the Mercury-Atlas 9 (MA-9) manned 1-day mission were published. This was the ninth flight of a production Mercury spacecraft to be boosted by an Atlas launch vehicle and the sixth manned United States space flight. According to plans, MA-9 would complete almost 22 orbits and be recovered approximately 70 nautical miles from Midway Island in the Pacific Ocean. Primary objectives of the flight were to evaluate the effects of the space environment on an astronaut after more than 1 but less than 2 days in orbit. During this period, close attention would be given to the astronaut's ability to function as a primary operating system of the spacecraft while in a sustained period of weightlessness. The capability of the spacecraft to perform over the extended period of time would be closely monitored. From postflight information, data would be available from the pilot and the spacecraft to ascertain, to a degree, the feasibility of space flights over a much greater period of time - Project Gemini, for example. In addition, the extended duration of the MA-9 mission provided a check on the effectiveness of the worldwide tracking network that could assist in determining the tracking requirement for the advanced manned space flight programs.

NASA Project Mercury Working Paper No. 232, subject: Manned One-Day Mission Directive for Mercury-Atlas 9 (M-9, spacecraft 20), Feb. 12, 1963.

The Manned Spacecraft Center announced a mid-May flight for Mercury-Atlas 9 (MA-9). Originally scheduled for April, the launch date was delayed by a decision to rewire the Mercury-Atlas flight control system, as a result of the launch vehicle checkout at the plant inspection meeting.

MSC Release 63-26, Feb. 12, 1963.

February 18-22

The McDonnell Aircraft Corporation reported to the Manned Spacecraft Center on the results of Project Orbit Run 109. This test run completed a 100-hour full-scale simulated mission, less the reaction control system operation, to demonstrate the 1-day mission capability of the Mercury spacecraft. Again, as in earlier runs, the MA-9/20 flight plan served as the guideline, including the use of onboard supplies of electrical power, oxygen, and coolant water, with hardline controls simulating astronaut functions. During the 2-hour prelaunch hold, a small leak was suspected in the secondary oxygen system, but at the end of the hold all systems indicated a "GO" condition and the simulated launch began. System equipment programing started and was recycled at the end of each 22 simulated orbits covering 33 mission hours. Test objectives were attained without any undue difficulty.

Letter, McDonnell Aircraft Corporation to NASA-MSC, subject: Contract NAS 5-59, Project Mercury, Model 133L, Project Orbit Spacecraft No. 9A T+ 3 Day Test Report, Category IV-I, Run 109, Transmittal of, March 5, 1963.

February 20

Kenneth S. Kleinknecht, Manager, Mercury Project Office, commented on the first anniversary of the Glenn flight (MA-6) that 1,144.51 minutes of orbital space time had been logged by the three manned missions to date. These flights proved that man could perform in a space environment and was an important and integral part of the mission. In addition, the flights proved the design of the spacecraft to be technically sound. With the excellent cooperation extended by the Department of Defense, other government elements, industry, and academic institutions, a high level of confidence and experience was accrued for the coming Gemini and Apollo projects.

MSC Release 63-20, Feb. 20, 1963.

The Smithsonian Institution received the Friendship 7 spacecraft (MA-6 Glenn flight) in a formal presentation ceremony from Dr. Hugh L. Dryden, the NASA Deputy Administrator. Astronaut John Glenn presented his flight suit, boots, gloves, and a small American flag that he carried on the mission.

Information supplied by Albert M. Chop, Deputy Public Affairs Officer, Public Affairs Office, MSC, Feb. 21, 1963.

In announcing a realignment of the structure of the Office of Manned Space Flight, Director D. Brainerd Holmes named two new deputy directors and outlined a changed reporting structure. Dr. Joseph F. Shea was appointed Deputy Director for Systems, and George M. Low assumed duties as Deputy Director for Office of Manned Space Flight Programs. Reporting to Dr. Shea would be Director of Systems Studies, Dr. William A. Lee; Director of Systems Engineering, John A. Gautrand; and Director of Integration and Checkout, James E. Sloan. Reporting to Low would be Director of Launch Vehicles, Milton Rosen; Director of Space Medicine, Dr. Charles Roadman; and Director of Spacecraft and Flight Missions, presently vacant. Director of Administration, William E. Lilly, would provide administrative support in both major areas.

February 21

Gordon Cooper and Alan Shepard, pilot and backup pilot, respectively, for the Mercury-Atlas 9 (MA-9) mission, received a 1-day briefing on all experiments approved for the flight. Also at this time, all hardware and operational procedures to handle the experiments were established.

NASA-MSC Report, Project Mercury (MODM Project) [Quarterly] Status Report No. 18 for Period Ending April 30, 1963.

The McDonnell Aircraft Corporation notified the Manned Spacecraft Center that the ultra high frequency transceivers were being prepared for the astronaut when in the survival raft. During tests of these components, an effective range of 5 to 10 miles had been anticipated, but the actual average range recorded by flyovers was 12 miles. Later, some faults were discovered in the flyover monitoring equipment, so that with adjustments the average range output was approximately 20 miles.

Letter, McDonnell Aircraft Corporation to NASA-MSC, subject: Contract NAS 5-59, Project Mercury, Model 133L, UHF Transceiver Power Output, Feb. 21, 1963.

February 23

Manned Spacecraft Center checkout and special hardware installation at Cape Canaveral on spacecraft 20 were scheduled for completion as of this date. However, work tasks were extended for a 2-week period because of the deletion of certain experimental hardware - zero g experiment and new astronaut couch. In addition, some difficulties were experienced while testing the space reaction control system and environmental control system.

Activity Report, MSC-Atlantic Missile Range Operations, January 27-February 23, 1963.

February (during the month)

The Air Force Aeronautical Chart and Information Center published the 22-orbit version of the worldwide Mercury tracking chart. The version of August 1962 covered 18 orbits.

Mercury Orbit Chart MOC-6, 1st ed., USAF Aeronautical Chart and Information Center, Feb. 1963.

March 1

Spacecraft 9A, configured for manned 1-day mission requirements, completed Project Orbit Run 110. For this test, only the reaction control system was exercised; as a result of the run, several modifications were made involving pressurization and fuel systems.

NASA-MSC Report, Project Mercury (MODM Project) [Quarterly] Status Report No. 18 for Period Ending April 30, 1963.

March 5

NASA Headquarters published a study on the ejection of an instrument package from an orbiting spacecraft. By properly selecting the ejection parameters, the package could be positioned to facilitate various observation experiments. From this experiment, if successful, the observation acuity, both visual and electrical, could be determined; this data would assist the rendezvous portion of the Gemini flights.

NASA General Working Paper No. 10,005, subject: Parametric Study of Separation Distance and Velocity between a Spacecraft and an Ejected Object, March 5, 1963.

March 11

Based on a request from the Manned Spacecraft Center, McDonnell submitted a review of clearances between the Mercury spacecraft 15B retropack and the launch vehicle adapter during separation maneuvers. This review was prompted by the fact that additional batteries and a water tank had been installed on the sides of the retropack. According to the McDonnell study the clearance safety margin was quite adequate.

Letter, McDonnell Aircraft Corporation to NASA MSC, subject: Contract NAS 5-59, Project Mercury, Model 133L, Retropack-Adapter Clearance Study, March 11, 1963.

March 15

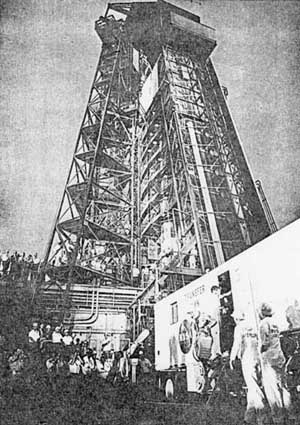

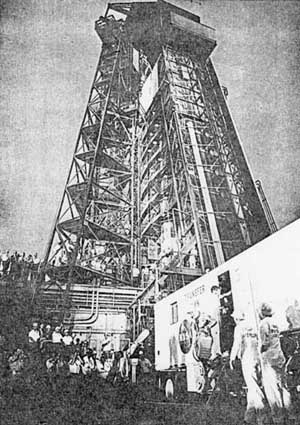

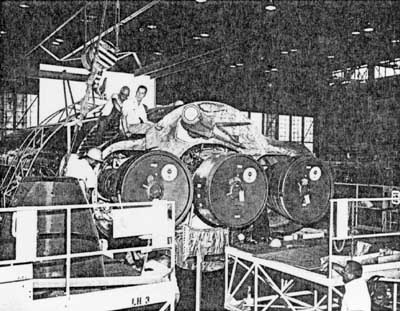

Factory roll-out inspection of Atlas launch vehicle 130 was conducted at General Dynamics some 15 days later than planned. Delay was due to a re-work on the flight control wiring. After the launch vehicle passed inspection, shipment was made to Cape Canaveral on March 18, 1963, (see fig. 66) and the launch vehicle was erected on the pad on March 21, 1963.

NASA-MSC Report, Project Mercury (MODM Project) [Quarterly] Status Report No. 18 for Period Ending April 30, 1963.

|

|

Figure 66. Atlas launch vehicle 130-D (MA-9) undergoing inspection at Cape Canaveral.

|

March 19

The Manned Spacecraft Center received a slow-scan television camera system, fabricated by Lear Siegler, Incorporated, for integration with the Mercury-Atlas 9 (MA-9) mission. This equipment, weighing 8 pounds, could be focused on the pilot or used by the astronaut on other objects inside the spacecraft or to pick up exterior views. Ground support was installed at three locations - Mercury Control Center, the Canary Islands, and the Pacific Command Ship - to receive and transmit pictures of Cooper's flight. Transmission capabilities were one picture every 2 seconds.

MSC Release 63-52, March 19, 1963.

March 22

The National Rocket Club presented to John Glenn, pilot of America's first orbital manned space flight, the Robert H. Goddard trophy for 1963 for his achievement in assisting the advance of missile, rocket, and space flight programs.

MSC Release 63-54, March 20, 1963.

March 28

For the purpose of reviewing the MA-9 acceleration profile, pilot Gordon Cooper and backup pilot Alan Shepard received runs on the Johnsville centrifuge.

NASA-MSC Report, Project Mercury (MODM Project) [Quarterly] Status Report No. 18 for Period Ending April 30, 1963.

April 5-6

Gordon Cooper and Alan Shepard, MA-9 pilot and backup pilot, visited the Morehead Planetarium in North Carolina to review the celestial sphere model, practice star navigation, and observe a simulation of the flashing light beacon (an experiment planned for the MA-9 mission).

NASA-MSC Report, Project Mercury (MODM Project) [Quarterly] Status Report No. 18 for Period Ending April 30, 1963.

April 9

Langley Research Center personnel visited Cape Canaveral to provide assistance in preparing the tethered balloon experiment for the Mercury-Atlas 9 (MA-9) mission. This work involved installing force measuring beams, soldered at four terminals, to which the lead wires were fastened.

Memo, Thomas Vranas to Associate Director, Langley Research Center, subject: Trip to Cape Canaveral to Rectify Difficulties in Strain Gage Instrumentation, April 25, 1963.

April 10-11

Full-scale recovery and egress training was conducted for Gordon Cooper and Alan Shepard in preparation for the MA-9 mission. During the exercise, egresses were effected from the spacecraft with subsequent helicopter pickup and dinghy boarding. The deployment and use of survival equipment were also practiced.

NASA-MSC Report, Project Mercury (MODM Project) [Quarterly] Status Report No. 18 for Period Ending April 30, 1963.

April 15

The Manned Spacecraft Center published a detailed flight plan, and the assumption was made that the mission would be nominal, with any required changes being made by the flight director. Scheduled experiments, observations, and studies would be conducted in a manner that would not conflict with the operational requirements. Due to the extended duration of the flight, an 8-hour sleep period was programed, with a 2-hour option factor as to when the astronaut would begin his rest period. This time came well within the middle phases of the planned flight and would allow the astronaut ample opportunity to be in an alert state before retro-sequence. In addition to the general guidelines, the astronaut had practically a minute-to-minute series of tasks to accomplish.

MA-9/20 Flight Plan, prepared by Spacecraft Operations Branch, Flight Crew Operations Division, MSC, April 15, 1963.

April 16-17

An MA-9 mission briefing was conducted for the astronauts and Mercury support personnel. Subjects under discussion included recovery procedures, network communications, spacecraft systems, flight plan activities, and mission rules.

NASA-MSC Report, Project Mercury (MODM Project) [Quarterly] Status Report No. 18 for Period Ending April 30, 1963.

April 20

The final water condensate tank was installed in spacecraft 20 for the MA-9 mission. In all, the system consisted of a 4-pound, built-in tank, a 3.6 pound auxiliary tank located under the couch head, and six 1-pound auxiliary plastic containers. The total capacity for condensate water storage was 13.6 pounds. In operation, the astronaut hand-pumped the fluid to the 3.6 pound tank to avoid spilling moisture inside the cabin from the built-in tank. Then the 1-pound containers were available.

Report, subject: Project Mercury Weekly Report 29, Spacecraft 20, April 21-27, 1963.

April 22

Spacecraft 20 was moved from Hanger S at Cape Canaveral to Complex 14 and mated to Atlas launch vehicle 130-D in preparation for the Mercury-Atlas 9 (MA-9) mission. The first simulated flight test was begun immediately.

Report, subject: Project Mercury Weekly Report 29, Spacecraft 20, April 21-27, 1963.

The Bendix Corporation reported to the Manned Spacecraft Center that it had completed the design and fabrication of an air lock for the Mercury spacecraft. This component was designed to collect micrometeorites during orbital flight. Actually the air lock could accommodate a wide variety of experiments, such as ejecting objects into space and into reentry trajectories, and exposing objects to a space environment for observation and retrieval for later study. Because of the modular construction, the air lock could be adapted to the Gemini and Apollo spacecraft.

Letter, Bendix Corporation to NASA-MSC, subject: Bendix Utica Air Lock for Mercury Spacecraft, April 22, 1963, with inclosures.

Scott Carpenter told an audience at the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics' Second Manned Space Flight Meeting in Dallas, Texas, that the Mercury program would culminate with the 1-day mission of Gordon Cooper.

Paper, subject: Flight Experiences in the Mercury Program, presented by M. Scott Carpenter, NASA MSC at the AIAA 2nd Manned Space Flight Meeting, Dallas, Texas, April 22, 1963.

After spacecraft 20 was mated to Atlas launch vehicle 130-D, a prelaunch electrical mate and abort test and a joint flight compatibility test were made. During the latter, some difficulty developed in the flight control gyro canisters, causing replacement of the components; a rerun of this portion of the test was scheduled for May 1, 1963.

NASA-MSC Report, Project Mercury (MODM Project) [Quarterly] Status Report No. 18 for Period Ending April 30, 1963.

April 30

As of this date, a number of improvements had been made to the Mercury pressure suit for the Mercury-Atlas 9 (MA-9) flight. (See fig. 67.) These included a mechanical seal for the helmet, new gloves with an improved inner-liner and link netting between the inner and outer fabrics at the wrist, and an increased mobility torso section. The MA-9 boots were integrated with the suit to provide additional comfort for the longer mission, to reduce weight, and to provide an easier and shorter donning time. Another change relocated the life vest from the center of the chest to a pocket on the lower left leg. This modification removed the bulkiness from the front of the suit and provided for more comfort during the flight. These are but a few of the changes.

NASA-MSC Report, Project Mercury (MODM Project) [Quarterly] Status Report No. 18 for Period Ending April 30, 1963; information supplied by James McBarron, Crew Systems Division, MSC, May 13, 1963.

|

|

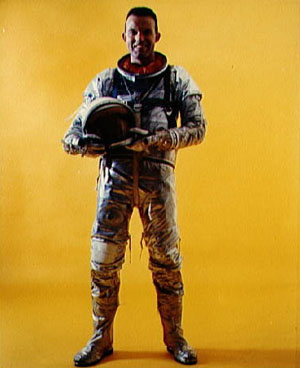

Figure 67. Flight pressure suit of astronaut L. Gordon Cooper used in MA-9, 22-orbit mission. Compare with flight pressure suit of astronaut Alan Shepard in MR-3 suborbital flight in figure 37.

|

May 12

Dr. Charles A. Berry, Chief, Aerospace Medical Operations Office, Manned Spacecraft Center, pronounced Gordon Cooper in excellent mental and physical condition for the upcoming Mercury-Atlas 9 (MA-9) mission.

MA-9 Advisory, Mercury Atlantic News Center, May 12, 1963.

May 12-19

Some 1,020 reporters, commentators, technicians, and others of the news media from the U.S. and several foreign countries gathered at Cape Canaveral, with another 130 at the NASA News Center in Hawaii, to cover the Mercury-Atlas 9 (MA-9) mission. Over the course of these days at Cape Canaveral, Western Union estimated that approximately 600,000 words of copy were filed, of which 140,000 were transmitted to European media. This does not include stories phoned in by reporters nor copy filed from the Pacific News Center, or for radio and TV coverage. During the 546,167-statute-mile flight, television audiences could see the astronaut or views inside and outside the spacecraft from time to time. Approximately 1 hour and 58 minutes were programed. Visual coverage was relayed to Europe via satellites.

Observed by author; Western Union statistics supplied by John J. Peterson, Manager, Mercury Atlantic News Center, May 19, 1963.

May 14

An attempt was made to launch Mercury-Atlas 9 (MA-9), but difficulty developed in the fuel pump of the diesel engine used to pull the gantry away from the launch vehicle. This involved a delay of approximately 129 minutes after the countdown had reached T-60 minutes. After these repairs were effected, failure at the Bermuda tracking station of a computer converter, important in the orbital insertion decision, forced the mission to be canceled at T-13 minutes. At 6:00 p.m. e.d.t., Walter C. Williams reported that the Bermuda equipment had been repaired, and the mission was rescheduled for May 15, 1963.

May 15-16

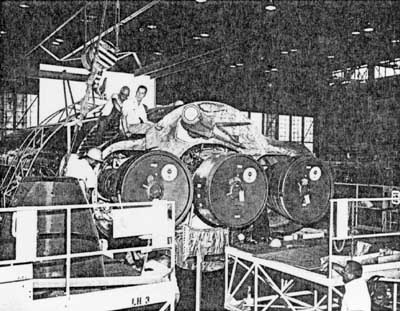

Scheduled for a 22-orbit mission, Mercury-Atlas 9 (MA-9), designated Faith 7, was launched from Cape Canaveral at 8:04 a.m. e.d.t., with astronaut L. Gordon Cooper as the pilot. (See fig. 68.) Cooper entered the spacecraft at 5:33 a.m. the morning of May 15, and it was announced over Mercury Control by Lt. Colonel John A. Powers that "barring unforeseen technical difficulties the launch would take place at 8:00 a.m. e.d.t." As a note of interest, Cooper reported that he took a brief nap while awaiting the launch. The countdown progressed without incident until T-11 minutes and 30 seconds when some difficulty developed in the guidance equipment and a brief hold was called. Later, a momentary hold was called at T-19 seconds to determine whether the systems went into automatic sequencing, which occurred as planned. The liftoff was excellent, and visual tracking could be made for about 2 minutes through a cloudless sky. The weather was considerably clearer than on the day before. The Faith 7 flight sequencing - booster engine cut off, escape tower jettison, sustainer engine cut off - operated perfectly and the spacecraft was inserted into orbit at 8:09 a.m. e.d.t. at a speed that was described as almost unbelievably correct. The perigee of the flight was about 100.2 statute miles, the apogee was 165.9, and Faith 7 attained a maximum orbital speed of 17,546.6 miles per hour. During the early part of the flight, Cooper was busily engaged in adjusting his suit and cabin temperatures, which were announced as 92 degrees and 109 degrees F, respectively, well within the tolerable range. By the second orbit, temperature conditions were quite comfortable, so much so, in fact, that the astronaut took a short nap. During the third orbit, Cooper deployed the flashing light experiment successfully and reported that he was able to see the flashing beacon on the night side of the fourth orbit. Thus Cooper became the first man to launch a satellite (the beacon) while in orbital flight. Another experiment was attempted after 9 hours in flight, during the sixth orbit, when Cooper tried to deploy a balloon but this attempt met with failure. A second deployment effort met with the same results. During this same orbit (sixth), the astronaut reported that he saw a ground light in South Africa and the town from which it emanated. This was an experiment to evaluate an astronaut's capability to observe a light of known intensity and to relate its possible applications to the Gemini and Apollo programs, especially as it pertained to the landing phases. After the beginning of the eighth orbit, Faith 7 entered a period of drifting flight - that is, the astronaut did not exercise his controls - and this drifting condition was programed through the fifteenth orbit. Some drifting flight had already been accomplished. Since the astronaut's sleep-option period was scheduled for this flight phase, Cooper advised the telemetry command ship, Rose Knot Victor off the coast of Chile, just before the ninth orbit that he planned to begin his rest period. The astronaut contacted John Glenn off the coast of Japan while in the ninth orbit, but lapsed into sleep shortly after entering the 10th orbit. During his sleep period, suit temperature rose slightly, and the astronaut roused, reset the control, and resumed his rest. Cooper contacted Muchea, Australia, during the 14th orbit after a restful night of drifting flight and resumed his work program. He reported just before entering the 17th orbit that he was attempting to photograph the zodiacal light. While in the 19th orbit, the first spacecraft malfunction of concern occurred when the .05g light appeared on the instrument panel as Cooper was adjusting the cabin light dimmer switch. The light, sensitive to gravity, normally lights during reentry. The flight director instructed Cooper to power up his attitude control system and to relay information on attitude indications reception on his gyros. All telemetry data implied that there had been no orbital decay and that the speed of Faith 7 was correct. The obvious conclusion was that the light was erroneous. Inspectors were later of the opinion that water in the system had caused a short circuit and had tripped a relay, causing the light to appear. Because of this condition, the flight director believed that certain portions of the automatic system would not work during reentry, and the astronaut was advised to reenter in the manual mode, becoming the first American to use this method exclusively for reentry. During the reentry operation, Cooper fired the retrorockets manually, by pushing a button for the first of three rockets to start the sequence. He attained the proper reentry attitude by using his observation window scribe marks to give proper reference with the horizon and to determine if he were rolling. John Glenn, aboard the command ship off the Japanese coast provided the countdown for the retrosequence and also advised Cooper when to jettison the retropack. The main chute deployed at 11,000 feet. Faith 7 landed 7,000 yards from the prime recovery ship, the carrier USS Kearsarge, after a 34-hour, 19-minute, and 49-second space flight. Cooper did not egress from the spacecraft until he was hoisted aboard the carrier. The mission was an unqualified success. During the flight the use of consumables - electrical power, oxygen, and attitude fuel - ran considerably below the flight plan. On the 15th orbit 75 percent of the primary supply of oxygen remained, and the reserve supply was untouched. The unusual low consumption rate of all supplies prompted teasing by the Faith 7 communicators. They called the astronaut a "miser" and requested that he "stop holding his breath."

MA-9 Transcript, May 15, 1963.

|

|

Figure 68. Astronaut L. Gordon Cooper prepares for insertion in Faith 7 (MA-9) atop Mercury-Atlas gantry for 22-orbit flight.

|

May 15

As of this date, the number of contractor personnel at Cape Canaveral directly involved in supporting Project Mercury were as follows: McDonnell, 251 persons for Contract NAS 5-59 and 23 persons for spacecraft 15B (MA-10 work); Federal Electric Corporation, 8. This report corresponded with the launch date of astronaut Gordon Cooper in the Mercury-Atlas 9 (MA-9).

Memo, Harold G. Collins, Contracting Officer, to Director for Mission Requirements, subject: MSC/Cape Monthly Report on Contractor Personnel Headcount, May 17, 1963.

May 19

On a national televised press conference, emanating from Cocoa Beach, Florida, astronaut Gordon Cooper reviewed his experiences aboard the Faith 7 during the Mercury-Atlas 9 (MA-9) mission. Cooper, in his discussion, proceeded systematically throughout the mission from countdown through recovery. He opened his comments by complimenting Calvin Fowler of General Dynamics for his fine job on the console during the Atlas launching. During the flight, he reported that he saw the haze layer formerly mentioned by Schirra during the Sigma 7 flight (MA-8) and John Glenn's "fireflies" (MA-6). As for the sleep portion, Cooper felt he had answered with finality the question of whether sleep was possible in space flight. He also mentioned that he had to anchor his thumbs to the helmet restraint strap to prevent his arms from floating, which might accidently trip a switch. Probably the most astonishing feature was his ability visually to distinguish objects on the earth. He spoke of seeing an African town where the flashing light experiment was conducted; he saw several Australian cities, including the large oil refineries at Perth; he saw wisps of smoke from rural houses on the Asiatic Continent; and he mentioned seeing Miami Beach, Florida, and the Clear Lake area near Houston. With reference to particular problems while in flight, the astronaut told of the difficulties he experienced with the condensate water pumping system. During the conference, when Dr. Robert C. Seamans was asked about the possibilities of a Mercury-Atlas 10 (MA-10) flight, he replied that "It is quite unlikely."

MA-9 Press Conference, May 19, 1963.

May 21

In a White House ceremony, President John F. Kennedy presented astronaut Gordon Cooper with the NASA Distinguished Service Medal. Other members of the Mercury operations team receiving medals for outstanding leadership were as follows: G. Merritt Preston, Manager of Project Mercury Operations at Cape Canaveral; Floyd L Thompson, Langley Research Center; Kenneth S. Kleinknecht, Manager of the Mercury Project Office; Christopher C. Kraft, Director of Flight Operations Division, Manned Spacecraft Center; and Major General Leighton I. Davis, Commander, Air Force Missile Test Center.

NASA Historical Office, Astronautics and Aeronautics, May 1963.

May 22

President Kennedy at a regular press conference responded to a question regarding the desirability of another Mercury flight by saying that NASA should and would make that final judgement.

Transcript, New York Times, May 23, 1963, p. 18.

May 24

William M. Bland, Deputy Manager, Mercury Project Office, told an audience at the Aerospace Writers' Association Convention at Dallas, Texas, that "contrary to common belief, the Mercury spacecraft consumables have never been stretched like a rubber band to their limit in performing any of the missions." He pointed out that consumables such as electrical power, coolant water, oxygen, and carbon dioxide absorption were always available with large safety margins at the close of the flights. For example, astronaut Walter Schirra had a 9-hour primary oxygen supply at the end of his flight.

Paper, William M. Bland, Jr. and Lewis R. Fisher, Project Mercury Experience.

May 29

The Department of Defense submitted a summary of its support of the Mercury-Atlas 9 (MA-9) mission, with a notation that the department was prepared to provide support for the MA-10 launch. Other than the provision of the Atlas launch vehicle, the Department of Defense supplied the Air Force Coastal Sentry Quebec, positioned south of Japan to monitor and backup retrofire for orbits 6, 7, 21, and 22. In the southeast Pacific, the Atlantic Missile Range telemetry command ship Rose Knot Victor was positioned to provide command coverage for orbits 8 and 13. At a point between Cape Canaveral and Bermuda, the Atlantic Missile Range C-band radar ship Twin Falls Victory was stationed for reentry tracking, while the Navy's Range Tracker out of the Pacific Missile Range provided similar services in the Pacific. Other Department of Defense communications support included fixed island stations and aircraft from the several services. Rear Admiral Harold G. Bowen was in command of Task Force 140, positioned in the Atlantic Ocean in the event of recovery in that area. In addition, aircraft were available at strategic spots for sea recovery or recovery on the American or African Continents. In the Pacific, recovery Task Force 130, under the command of Rear Admiral C.A. Buchanan, was composed of one aircraft carrier and 10 destroyers. This force was augmented by aircraft in contingency recovery areas at Hickam; Midway Island; Kwajalein; Guam; Tachikawa, Japan; Naha, Okinawa; Clark Field, Phillippines; Singapore; Perth, Australia; Townsville; Nandi; Johnston Island; and Tahiti. Pararescuemen were available at all points except Kwajalein. The Middle East recovery forces (Task Force 109) were under the direction of Rear Admiral B.J. Semes and consisted of a seaplane tender and two destroyers supported by aircraft out of Aden, Nairobe, Maritius, and Singapore for contingency recovery operations. For bioastronautic support, the Department of Defense deployed 78 medical personnel, had 32 specialty team members on standby, committed 9 department hospitals and provided over 3,400 pounds of medical equipment. During the actual recovery, the spacecraft was sighted by the carrier USS Kearsarge (Task Force 130), and helicopters were deployed to circle the spacecraft during its final descent. Swimmers dropped from the helicopters to fix the flotation collar and retrieve the antenna fairing. Cooper remained in his spacecraft until he was hoisted aboard the carrier. A motor whaleboat towed the spacecraft alongside the ship.

Letter, Major General L.I. Davis, Department of Defense Representative Project Mercury/Gemini Support Operations, to Hon. Robert S. McNamara, Secretary of Defense, subject: Department of Defense Support of Project Mercury Manned One-Day Mission (MA-9), May 29, 1963.

Astronaut Gordon Cooper became the sixth Mercury astronaut to be presented with Astronaut Wings by his respective service.

NASA Historical Office, Astronautics and Aeronautics, May 1963.

June 6-7

Officials of the Manned Spacecraft Center made a presentation to NASA Administrator James E. Webb, outlining the benefits of continuing Project Mercury at least through the Mercury_Atlas 10 (MA-10) mission. They thought that the spacecraft was capable of much longer missions and that much could be learned about the effects of space environment from a mission lasting several days. This information could be applied to the forthcoming Projects Gemini and Apollo and could be gained rather cheaply since the MA-10 launch vehicle and spacecraft were available and nearing a flight readiness status.

MSC Weekly Activity Report, June 2-8, 1963.

June 8

In preparation for the Mercury-Atlas 10 (MA-10) mission, should the flight be approved by NASA Headquarters, several environmental control system changes were made in spacecraft 15B. Particularly involved were improvements in the hardware and flexibility of the urine and condensate systems. With regard to the condensate portion, Gordon Cooper, in his press conference, indicated that the system was not easy to operate during the flight of Faith 7 (MA-9).

MSC Weekly Activity Report, June 2-8, 1963.

June 12

Testifying before the Senate Space Committee, James E. Webb, the NASA Administrator, said: "There will be no further Mercury shots . . ." He felt that the manned space flight energies and personnel should focus on the Gemini and Apollo programs. Thus, after a period of 4 years, 8 months, and 1 week, Project Mercury, America's first manned space flight program, came to a close.

MSC, Space News Roundup, June 26, 1963.