Weathering the Recovery of Apollo 11

by Sean Potter, NASA Office of Communications

Last updated 2019-08-10

In the early morning hours of July 24, 1969, as the Apollo 11 crew slept quietly in the confined crew compartment of their Command Module, preparations were underway for their return to Earth following an eight-day journey that brought the first humans to the surface of the Moon.

As with the launch a week earlier, on July 16, weather was a critical factor in the success of the reentry of Apollo 11. With splashdown targeted to take place in the central Pacific, NASA flight controllers had to contend with a variety of factors – surface winds, winds aloft, wave height and the possibility of thunderstorms or, even worse, a tropical system.

To accurately predict weather conditions for the splashdown site, NASA turned to its colleagues at the U.S. Weather Bureau (now the National Weather Service), whose Spaceflight Meteorology Group (SMG) had been providing specialized weather forecasting decision support services since the days of Project Mercury.

Initially, the prime recovery area – where splashdown would occur – was located at 10.6° north by 172.5° west, about halfway between Howland Island and Johnston Atoll, approximately 1,000 nautical miles southwest of Honolulu, Hawaii.

At 171:53:47 into the mission (1:25:47 p.m. EDT July 23), CapCom Owen Garriott relayed the latest forecast for the recovery area to Commander Neil Armstrong. "Present forecast shows acceptable conditions in your recovery area – 2,000-foot scattered, high scattered, wind from 070 degrees, 13 knots, visibility 10 miles, and sea state about 4 feet," Garriott said. He also noted that the previous day's forecast had shown a tropical storm, Claudia, approximately 500 to 1,000 miles east of Hawaii, but noted satellite imagery taken that afternoon showed Claudia dissipating, "so this appears to be even less a factor than it was before," he added. Garriott also relayed information about another tropical storm, Viola, which was intensifying as it approached the Philippines, far to the west of the splashdown area. "Okay, sounds pretty good," Armstrong responded.

About 8.5 hours later, at 180:21:30 (9:53:30 p.m. EDT July 23), CapCom Bruce McCandless informed the crew to expect an update on the forecast. "We're going to be watching the weather here, and we expect to have an update on the weather, I guess, in about another half hour or 45 minutes, to pass to you."

At 181:42:06 (11:14:06 p.m. EDT July 23), Charlie Duke, who was now serving as CapCom, provided an update following a weather briefing he and Flight Director Gene Kranz had just received. "[T]he weather is clobbering in at our targeted landing point due to scattered thunderstorms," Duke told the crew. "We don't want to tangle with one of those, so we're going to move you – your aim point up-range. Correction, it'll be down-range, to target for a 1,500-nautical-mile entry, so we can guarantee uplift control."

The splashdown point was moved 215 nautical miles downrange – to 13.3° north by 169.2° west – an area where forecasters predicted conditions would be more ideal.

According to an article published by the Environmental Science Services Administration (ESSA, the predecessor of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and parent agency of the Weather Bureau) in October 1969, on July 22, SMG forecasters "saw an enlarged disturbed area just south of the planned landing site, but a Navy reconnaissance flight found no consequential weather north of 10 degrees latitude." The article noted that by the next day, "there were satellite indications that, by landing time, there might be trouble farther to the north. A Navy flight directed to that area found numerous showers and some thunderstorms."

The article goes on to say that a Weather Bureau forecaster in Honolulu, Richard Sasaki, "noted these indications of worsening weather" and contacted a representative from SMG, who, after conferring with Captain Willard 'Sam' Houston, commander of the Navy's Fleet Weather Central at Pearl Harbor, "recommended a northward shift of the landing area."

Houston, who, according to

his 2012 obituary, "was instrumental in developing modern weather forecasting technology including pioneering the use of weather satellites and computers," had taken command of Fleet Weather Central Pearl Harbor just one day before the Apollo 11 launch and was in a unique position to advise on the weather conditions at the recovery area. Not only was he in charge of forecasting weather for the crew's recovery, but he had top-secret clearance to view imagery from a classified military weather satellite program that eventually became the

Defense Meteorological Satellite Program (DMSP).

At nearby Hickam Air Force Base in Honolulu, Captain Hank Brandli had been monitoring imagery from the classified weather satellite and noticed signs of violent thunderstorm formation in the original Apollo 11 recovery area – a weather pattern he referred to as a "screaming eagle" thunderstorm, for the resemblance of the cloud patterns on the satellite imagery to an eagle's head. Such thunderstorms, whose tops can reach heights of 50,000 feet, develop out of tropical waves near the equator and are capable of producing gusty winds at the surface and shearing winds aloft, which would spell disaster for the Apollo 11 parachutes, which were deployed as the Command Module reached an altitude of 10,000 feet on its way toward splashdown.

As described in an

article published by the National Reconnaissance Office, Brandli shared the classified imagery with Houston, who, in turn, needed to convince Rear Admiral Donald C. Davis, commander of Task Force 130, the Navy's Pacific Recovery Forces for spacecraft missions such as Apollo 11, to reroute the aircraft carrier USS Hornet, the prime recovery ship for Apollo 11.

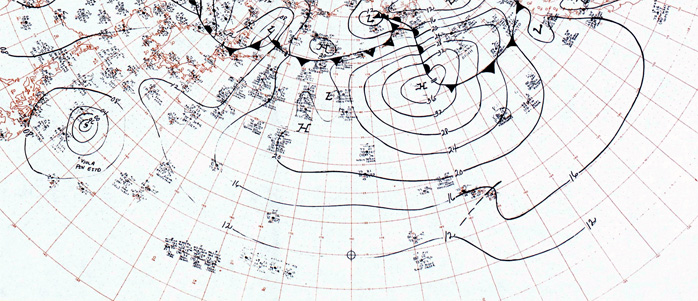

ATS-1 photograph (inset) showing the Pacific Ocean. ESSA-8 photograph (main image) showing the locations of the original and actual Apollo 11 landing area and the weather system that was in the area.

The DMSP satellite wasn't the only weather "eye in the sky" at the time, however. As noted by the ESSA article, NASA's

Applications Technology Satellite (ATS) also provided imagery of the recovery area. According to the article, based on ATS imagery and "other indications," SMG forecasters in Suitland, Maryland, "forecast 20-knot winds, six-foot seas, scattered showers and isolated thunderstorms with moderate to heavy turbulence." While the wind and sea forecast were apparently suitable for splashdown, "the NASA flight director and his staff did not want to risk the possible effects of turbulence on the Apollo's parachutes should the vehicle happen to come down in an active convective cloud."

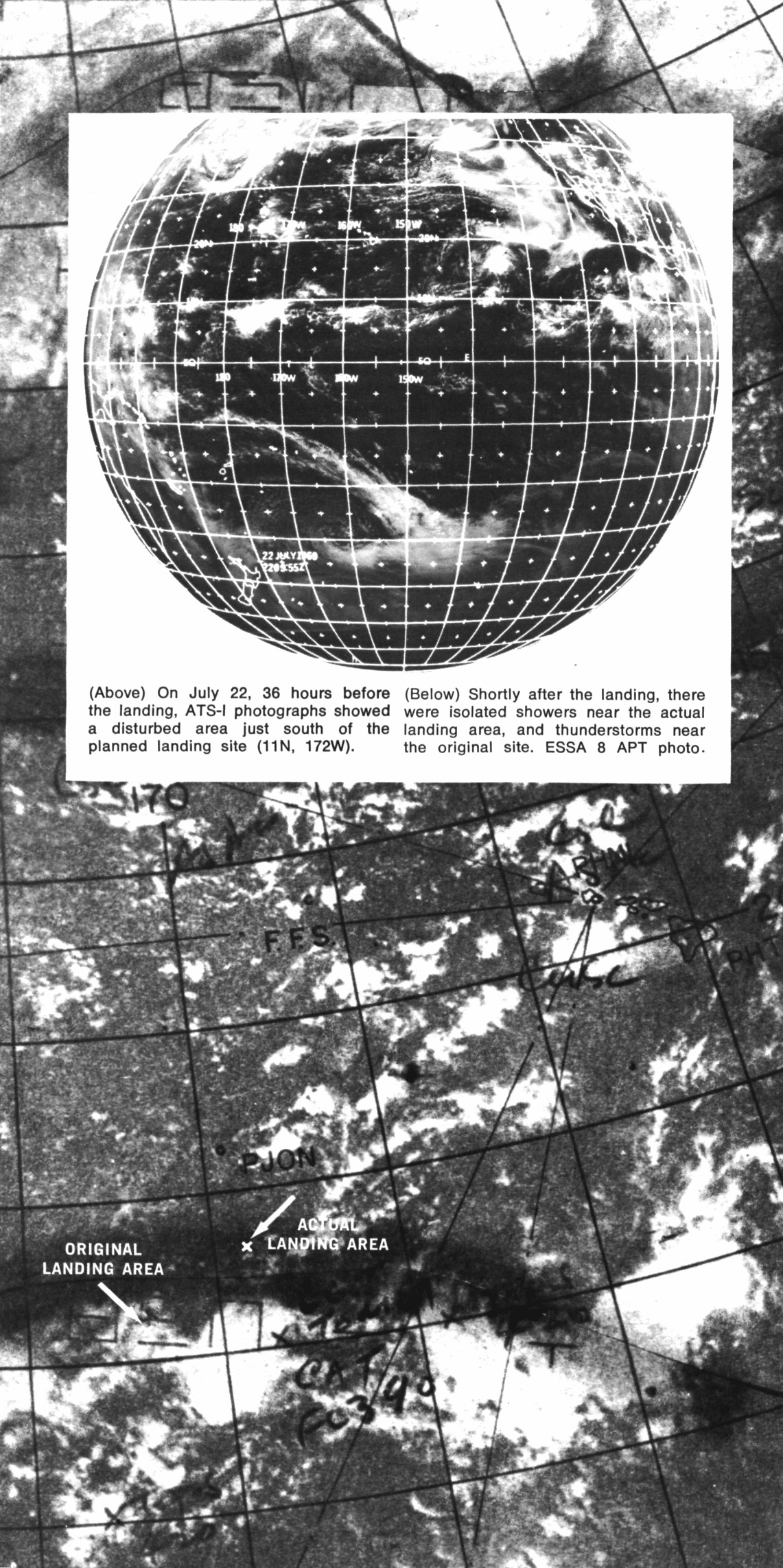

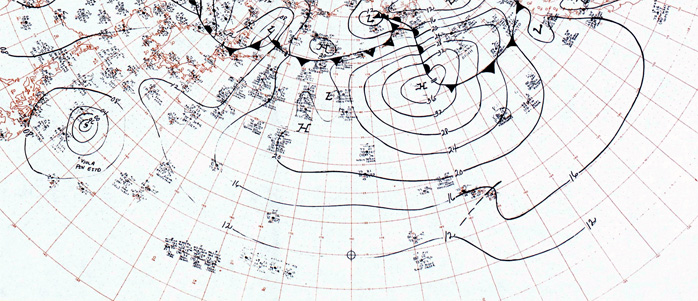

This is a cropped section of the Northern Hemisphere synoptic weather map (courtesy of NOAA) for 1200 GMT July 24, 1969 (about five hours prior to splashdown). Although difficult to read here, the station model plot near the bottom of the map, just to the right of center, is based on observations from a ship. It is located almost exactly at the site of splashdown and, therefore, it is possible these observations are from the USS Hornet or another ship involved in the recovery operations.

To ensure a safe recovery, the Command Module’s onboard computer was used to execute a maneuver known as a "skip-up" to lengthen the reentry trajectory and overfly the area of inclement weather. In a

technical crew debriefing that occurred on July 31, astronaut Michael Collins complained about having to increase the entry trajectory due to the weather. "Initially the weather in that area looked good, but as we got in closer, Houston started making grumbling noises about the weather in that recovery area," he said. "Finally they said there were thunderstorms there and they were going at 1,500 [nautical] miles. I wasn't very happy with that fact because the great majority of our practice and simulator work and everything else had been done on a 1,187 [nautical mile] target point."

Image ID: 6900604. The Apollo 11 crew, dressed in biological isolation garments, wait in a liferaft to be picked up by helicopter from beside their Command Module.

Splashdown occurred at 195:18:35 (12:50:35 p.m. July 24), at a point 1.69 nautical miles from the new target.

Weather conditions at the new splashdown site were excellent, with a visibility of 12 miles, wind speeds of 17 knots (19.5 mph) and 3 to 5 foot waves. There was about six-tenths cloud cover above 1,500 feet, but there was no precipitation.

In 2009,

Houston told an audience at the Naval Postgraduate School that a weather reconnaissance flight to the original splashdown location on July 24 observed the violent "screaming eagle" thunderstorms Brandli had seen forming – with tops even higher than he had predicted, at 60,000 feet. Houston later

received the Navy Commendation Medal for his services as commander of Fleet Weather Central in Pearl Harbor, "particularly for his timely warning of intense thunderstorms in the Apollo 11 recovery area which enabled the movement of recovery to calmer seas."

How much of a role the top-secret military satellite imagery Brandli shared with Houston played in the decision to move the recovery site is unclear. The 1969 ESSA article quotes the Weather Bureau's Kenneth Nagler, chief of the Office of Meteorological Operations, Space Operations Support Division (of which SMG was a part), in saying the decision to move the recovery area was made on the basis of SMG's forecasts. At the time, however, the DMSP imagery remained classified and it is likely that Nagler was not even aware of its existence. Regardless, Apollo 11's recovery is an example of meteorologists and decisionmakers working together to ensure the successful outcome of what was perhaps the most historic mission in America's space program.