Apollo 13 - Fifty Years On

Introduction to Journal Creation and Acknowledgements

Copyright © 2020 by W. David Woods, Johannes Kemppanen. All rights reserved.

Last updated 2020-02-14

Dedicated to everyone who took part in the Apollo Program and the crew of Apollo 13, to Jim, Jack, Fred, Ken, Joe, Vance, Jack L, John W. and Charlie, and for every grown up and child who has ever looked up to the skies or to the page of a book and felt the awe of space travel.

- J.K.

On the Importance of Preserving Apollo Documents

a foreword by

Emily Carney, the Space Hipster

As time marches on, we’ve seen how time and circumstances can sometimes ravage art and vital documentation. One example I can think of is Eva Hesse’s art, which was done in media including plastics and latex. The artist died in 1970, and since then, some of her pieces have degraded over time due to aging; those displaying her art and sculptures must take great care to preserve her historic pieces, as they represent an artist whose time on this Earth was all-too-brief.

I feel similarly about media connected to the Apollo program, especially Apollo 13. As many of us know, Apollo 13 became one of the more “famous” missions due to a near-crippling oxygen tank explosion sustained during its flight. While the 1995 Ron Howard movie is entertaining, nothing beats the actual words of the astronauts, flight controllers, and workers recorded during these difficult hours. The mission’s purpose transformed from going to the Moon to something two-fold: a rescue mission, and an opportunity for all personnel to band together, and bring the crew home safely.

In 1982, the mission’s command module pilot, John L. “Jack” Swigert, Jr., died after a short cancer battle. As time, again, marches on, we lose perspectives of key personnel, or lose sight of them. This is why historical preservation is key, and will be crucial to get the Apollo 13 story across – in full accuracy – for future generations. The Apollo Flight Journal is an invaluable resource in this regard.

- E.C.

An Introduction to this 50th anniversary version of the Apollo 13 Flight Journal

It was Gene Kranz who famously prescribed the work ethic of Mission Control as 'tough and competent' in the aftermath of the 1967 Apollo 1 fire. He wanted to evoke the accountability of the Flight Control team, to remind them to never forget the immense responsibility they had to carry. As I was reflecting on the work of researching and editing this Journal you are perusing, these words came to mind again. Perhaps I saw them on one of the Facebook space groups I often trawl for inspiration and for historical tidbits to enjoy and ruminate on. Gene's legendary reputation has made them into a slogan, a catchphrase that symbolises Mission Control as much as the headsets and pocket protectors. It has also given me a philosophical point of contact, an anchor, from where to continue on my analysis.

In writing history, these tenets ring as true as they do in the field of sending men to space while riding fantastically complicated rockets. There is a deep responsibility to the pursuit of the truth, narrated to the best of our ability. The story that is known as history is fickle, fluid and transient only. Papers yellow, get displaced, lost, or burnt in the greatest scourge history can face, the fire. The human memory fares even worse. Our minds are riddled with holes, errors, misunderstandings, fake memories we absorb from others or make up as we go, to fill in the gaps. Digital media formats give us an illusion of immortality, but those are equally vulnerable to the effects of time. A historian's responsibility is to attempt to create a snapshot of a past event as accurately as possible. Dare we call the end result the truth? Perhaps on occasion one gets close. Yet it is dangerous to become wholly convinced of the excellence of one's efforts. New evidence might surface, not seen before - a process that has taken place again and again during my work on this journal. Each generation writes its own histories of past events as well, often colored by whatever ideology predominates at the time. Ideas change and words change. New generations look at the actions of the old with new eyes. The core values of a space historian should still be the same as postulated by Gene Kranz. Tough and competent. Such powerful words yet I am tempted to add a third commandment, however. It is humility comes to mind as a suitable candidate to complete this paradigm.

Writing the history of manned spaceflight, and especially a particularly famous event such as Apollo 13, carries a great responsibility. There are many preconceptions and ideas, some wrong, that people tend to repeat year after year. Some go as far back as the actual mission itself and everything that surrounded it, while others have grown out of the popular culture depictions of Apollo 13. Most notably, the popular 1995 movie by Ron Howard is not a historical documentary, and has altered some events as it sees fit to deliver the most exciting narrative. The movie is created for the purpose of entertainment, not for education. As in most cases, the reality, however, tends to be even more fascinating and incredible than what any scriptwriter could have come up with. This has been a feeling that I have received time and again, while working on this Journal. From beneath the technical jargon, the terse exchange and scratchy radio messages, I have uncovered layers of meaning below that of the obvious - the elusive human aspect. We only know the words of the astronauts and the people in Mission Control, speaking into their microphones, tape recorders rolling and creating a copy of their words for future review. Hours of listening to their tones, their accents, their slip-ups and their profanity has allowed us to reach the human level. These were extraordinary people doing incredible things, but they were still just people, ones with discomforts, unsavory habits and personality quirks that both endeared them to others, and sometimes alienated themselves from them. Personalities shine through these exchanges, often spoken in mild tones, often shielded in in-jokes and the highly specialized jargon of spaceflight appropriated for humorous purposes to lighten the situation. What an exciting opportunity it has been as well!

My choice of 'humility' to represent the project also speaks of the role of teamwork, and the long chain of history writing. A historian is always standing on the shoulders of Titans - to borrow the name of the NASA official history on the Gemini program - in itself paraphrasing a much older metaphor often attributed to Sir Isaac Newton - and it applies here fully. Everyone involved in the composition of this Apollo 13 Journal has had the work of other to draw from, whether in inspiration, or to reference to, or skills to pass on as received during previous historical scholarship. We are proud to be part of this chain - hopefully not revealed to be the weakest, in the years to come.

Journal Preparation

Example from one page of the Technical Air to Ground Transcript. Note the tape numbering and the day:hour:minute:second format for time coding

The making of this Apollo 13 Flight Journal has been a long process. After the initial creation by David Woods with the assistance of Alexander Turhanov and Lennox Waugh, updates have been sporadic for several years due to other commitments. The Apollo Flight Journal is a voluntary project, with people with lives taking part in its creation. However, in 2019, rookie AFJ editor Johannes Kemppanen joined the team and offered his contribution in creating a more complete edition of the Apollo 13 Flight Journal. After 15 years of consuming the AFJ privately, he was welcomed to the team with a pile of Apollo documentation and the orders of taking a crash course in HTML editing. It was with these tools that Johannes began to work. Reading, poring over diagrams, writing, editing, drawing, coloring, debating. You are now looking at the result of two years of work.

For this 2020 commemorative edition, the whole 13 Journal has been completely overhauled. The HTML code has been edited to create a style corresponding to the layout of the most recent updated template as created by David Woods and Ben Feist. This HTML work was done using Notepad++ text editor. Typos, editing errors and transciption errors were detected and corrected. Maximum kudos must be given to Alexander Turhanov for his diligence in creating the original transcript files I have worked with, considering the very sparse number of these errors. Parts of the air to ground tapes were listened and compared to the transcript when it was unclear whether the written down depiction of words could truly be what was said. Theses corrections too were small in number, and the errors were likely down to the hurried transcription process made already in 1970. Attribution of utterances to each astronaut and other recorded speaker was also occasionally questioned, and corrected if necessary. The sometimes poor audio quality caused by the contingency was probably to blame for this issue. Approximately 1,300 new illustrations were prepared by Johannes Kemppanen, using all possible available sources to create the best visual record of the mission as well. Images were sourced from NASA electronic archives, captured from film reels and mission onboard photography, and reproduced from original drawings and diagrams. Photo and picture editing and recoloring was performed in MS Paint and GIMP. David Woods performed additional image correction and editing work to optimize the illustrations for online publication.

Naturally, the core of the Journal remains the true utterances of the astronauts and Mission Control personnel as captured on tape, as the first hand record of events, thoughts and feelings throughout the mission. These have been amended and commented on using the best possible sources available to us. Mission Reports, Mission Control reports, technical manuals, general spaceflight histories, biographies and film material have been used to create what we hope is the most accurate interpretation and presentation of the mission. Besides general Apollo operational procedures and hardware details, another emphasis was in describing the unusual ways the spacecraft involved had to perform to accomplish the successful return of the crew. This also includes the Apollo Guidance Computer. We have attempted to create an easy to approach introduction to the operation of the onboard computer, with the hope that this will inspire interested parties to learn more as well, without overwhelming other readers who are less keen to dwell deeper. While it is not my intention to try and teach the reader to operate the Apollo spacecraft, I wished to produce a certain experience of interactivity with the material at hand. If an important control panel or a procedure is mentioned, the reader will be provided to a closeup high resolution image of this particular part of the control panels. This has been done to support our goal of providing the most accurate depiction of Apollo spacecraft operations in the hopes of giving the reader a chance to in some ways understand the complexity - and sometimes the surprising simplicity - of spaceflight in 1970.

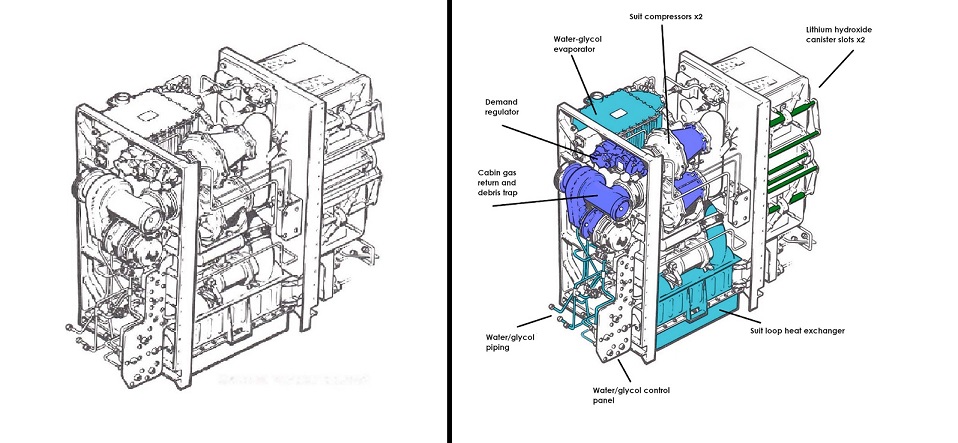

Example of image processing from black and white original to partially colored and annotated presentation.

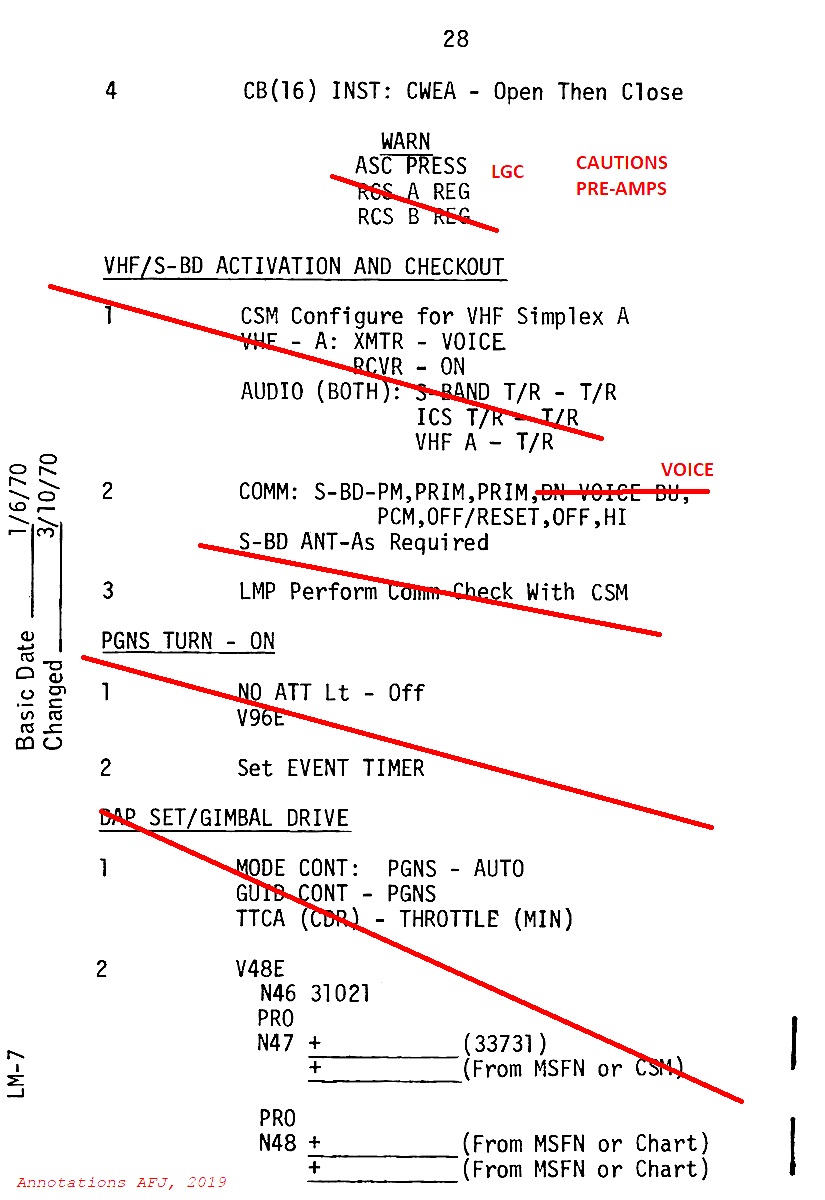

Example page of an onboard documentation, edited for the Journal.

Every piece of onboard documentation was reproduced with the best known fidelity to the original source material for the Journal. If the presented document contained editorial changes, such as annotations made to reflect those made onboard to adapt the material to the situation at hand, a legend was added onto each image to signify that AFJ editing had taken place on the document. If no changes are known to have been made, the onboard documentation was reproduced 'as is', and should correspond to what the crew had with them at the time.

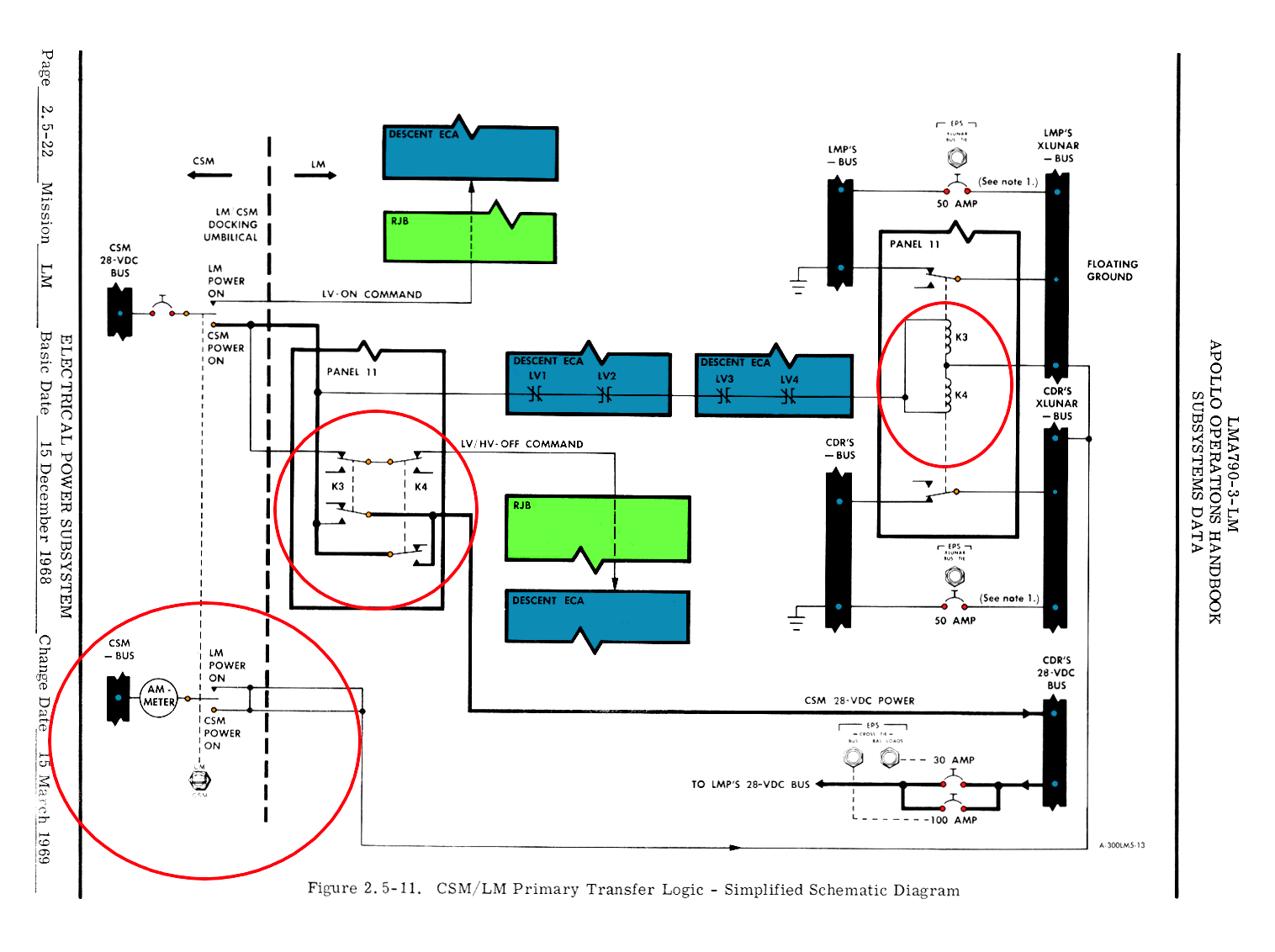

Color was added to original documentation imagery for clarity and emphasis.

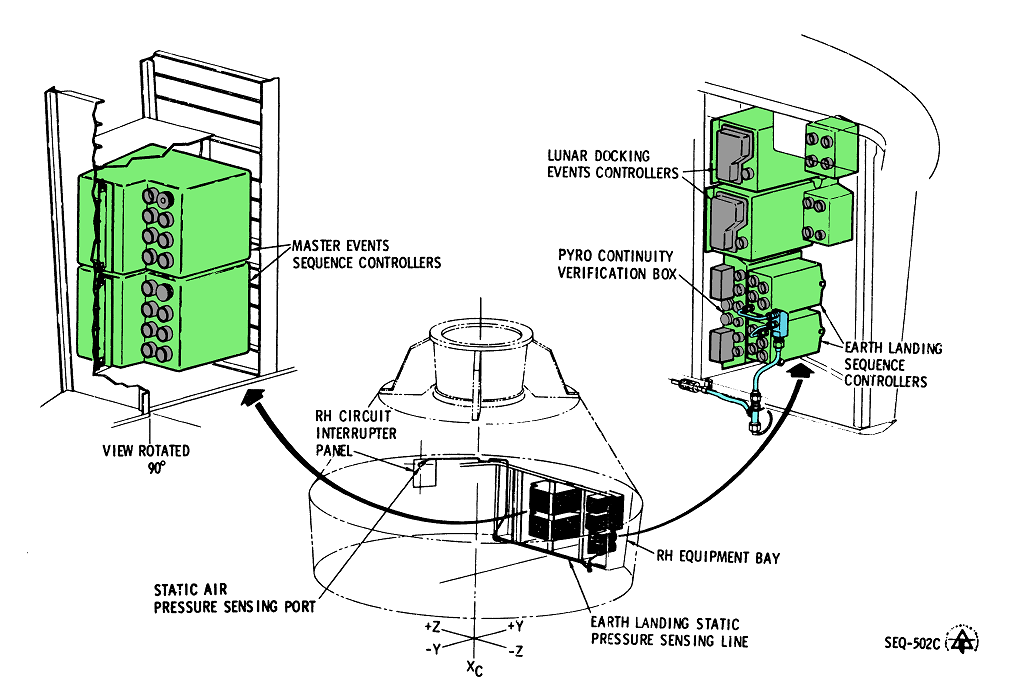

Images extracted from reference documentation such as the Apollo Operations Handbook (as above) were presented with the aim of maximizing clarity and educational value. Editing was done to remove any residual effects from image scanning process, and highlighting color was added for easier readibility and legibility. The original black and white materials are freely available online for anyone who wishes to browse them. For AFJ, we felt that the manipulation of secondary material such as these diagrams was something that improved their legibility and adds to the Journal as an educational resource. This extra ability to visualize the material is, we hope, of help to people wishing to learn more about these complex, fantastic machines.

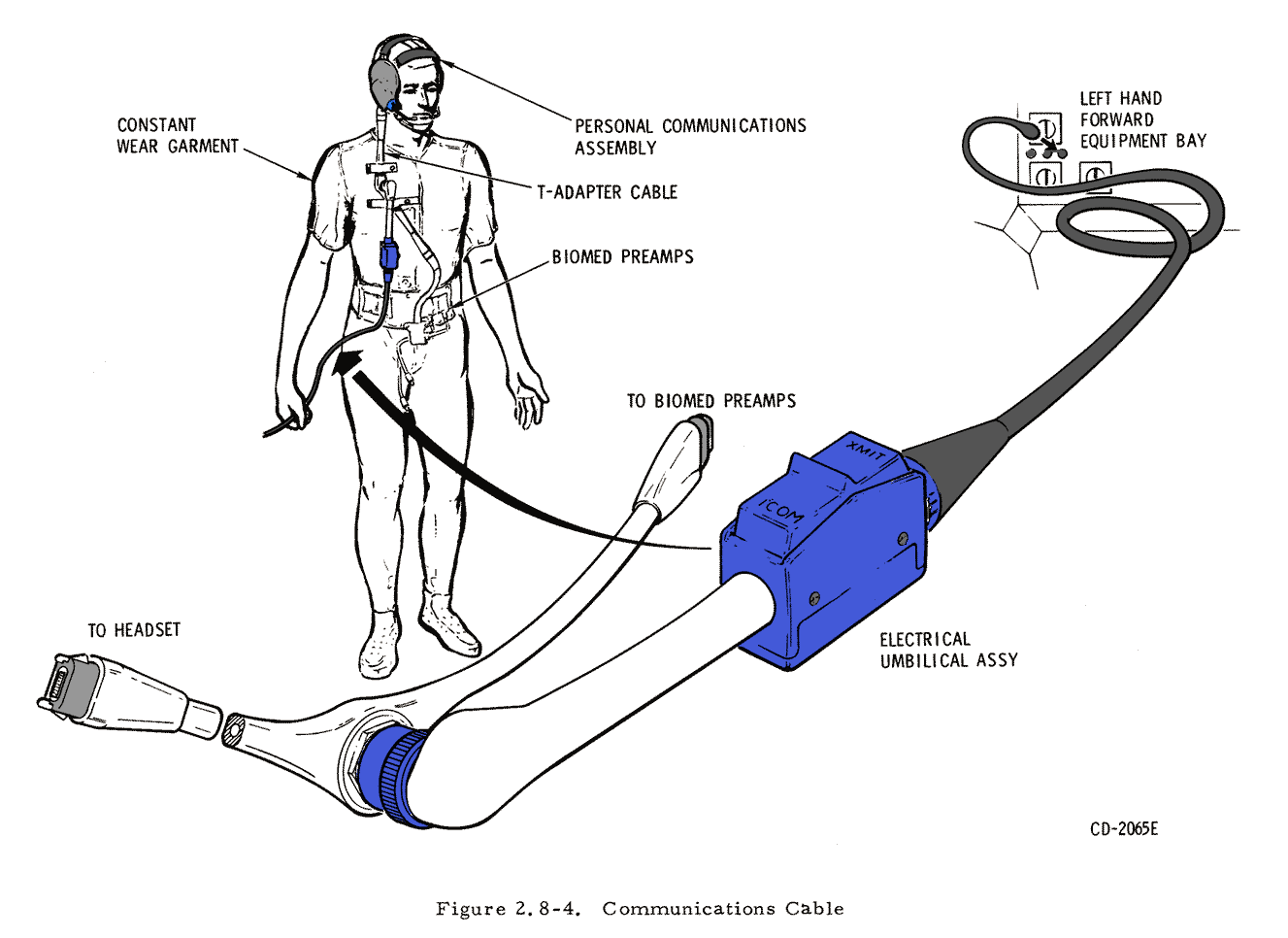

Example of natural colour being used in image editing.

Whenever possible, natural color was reproduced for graphic representations of onboard equipment. Photographs were then used to attempt to match the visual as closely as possible. Of course one has to understand that various lighting conditions existed while photographs were taken and hence any attempt to reproduce these colour is but an approximation. If the original coloring was not known or if such fidelity was not necessary, the most appropriate and clear color schemes were used to maximize clarity in interpretation of the images.

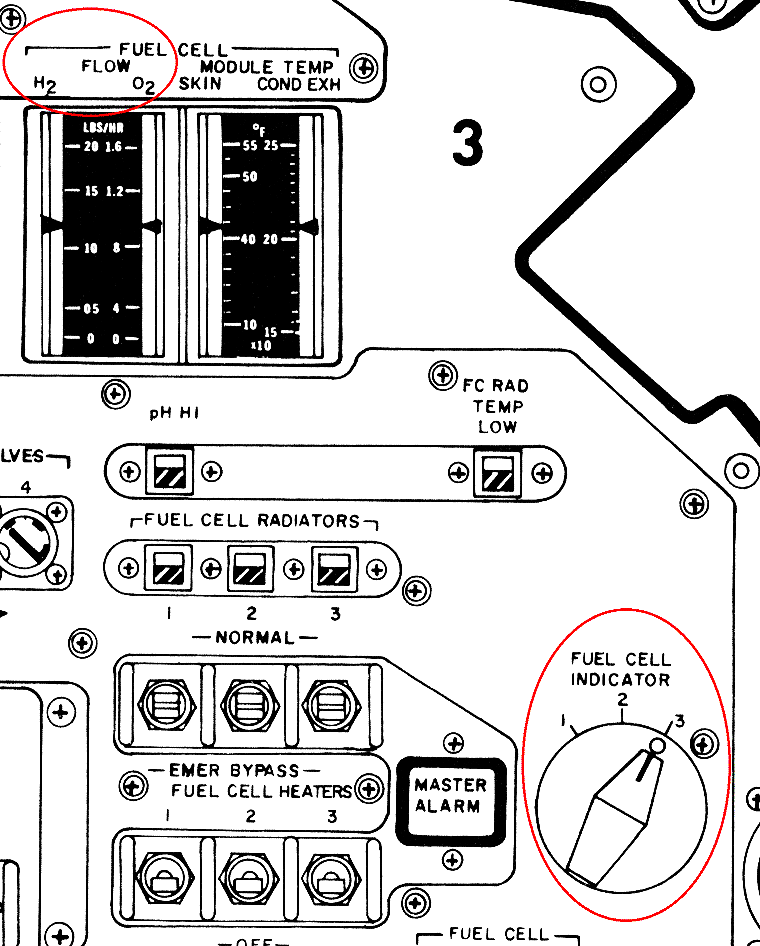

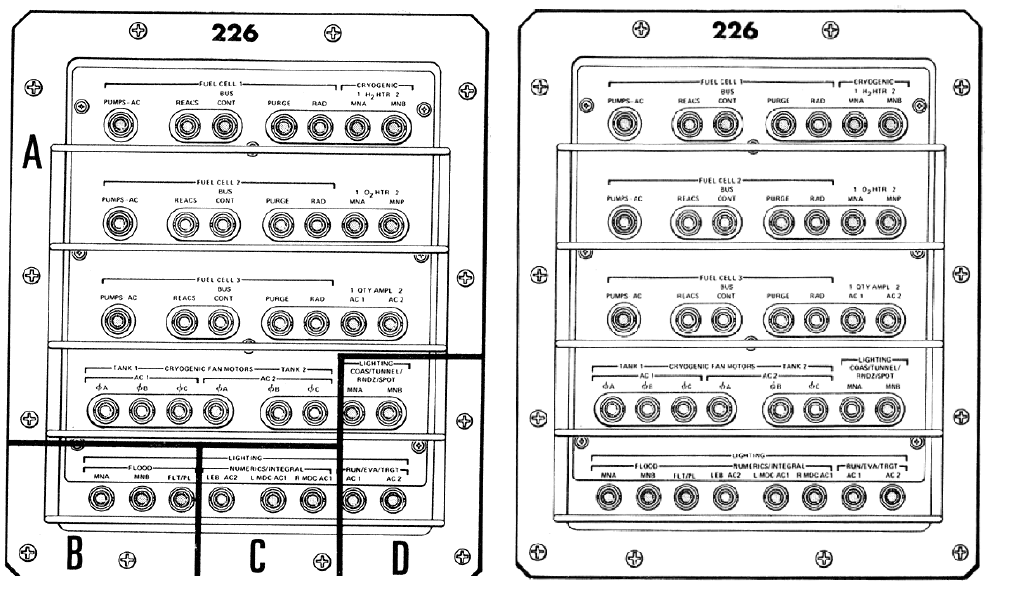

Highlighted control panel graphic. Original scan via heroicrelics.org.

High resolution scans of the onboard control panels were used to portray the crew interface onboard the Apollo spacecraft. While most of these panel images were presented as they are, occasionally highlighting was added to bring notice to the most crucial instruments being used at the moment. Care was taken to not to obstruct decals or other points of interest in the files. Image size was adjusted in the hopes of maintaining good legibility without sacrificing the ease of browsing or creating unneccessarily high bandwidth requirements.

Film capture from Mission Control.

Images were also captured from film sources, such as original film produced in Mission Control as well as onboard the Apollo spacecraft. While an attempt was made to place these captures into the transcript timeline as accurately as possible, occasionally we used them to illustrate other points where their inclusion added value to the presentation.

Colored and highlighted original page from technical documentation.

While images extracted from the original reference documentation were usually presented in an edited form to ensure clarity, occasionally we decided to include as much of the original page format as possible. This might included headers, page numbers and other elements of the original scanned page. Our hope was to allow the reader to have a little glimpse to the experience not only the original Apollo personnel did while browsing these documents, but also to that of the AFJ editing team, seeking for the best references to present here.

A control panel scan edited for clarity.

Some original scans required heavy editing for maximum legibility. The original presentation was not always of the sort that was best suited for public consumption or presentation in the current format, which led to the need for additional work to prepare the materials for publication. This too was done in the hope of adding value for the reader and the scholar. Much of this work was done to correct the errors created by digital conversion of paper or microfiche originals onto computer images.

Sources

The primary source of this edition of Apollo Flight Journal was the

transcription of the original air to ground communications that took place during the mission of Apollo 13. The Air to Ground loop consisted of the communications between the Apollo spacecraft and Mission Control in Houston. Additionally, we have included a transcription of the Public Announcements Officer commentary made during the mission, which has been sourced from other documentation. Digital copies of the original recordings available at

archive.org have been used as the basis for possible correction of the written record of the mission.

A great amount of technical documentation was required so as to properly interpret the technical jargon that permeates nearly every utterance aptured during the mission. The

The Apollo Operations Handbook Volume I , was a key document in defining onboard systems and their functionality, while also providing many illustrations. A similar document prepared for the Lunar Module,

as available here, was used to the same effect in regards to the LM. The amount of documents consulted for the creation of this journal numbers in the dozens.

Acknowledgements and Thanks

This work would not have been possible without the help and support of many people over the years. Space archivist Bob Andrepont's collection of NASA documents online was simply invaluable as source material for my research. Some of these materials were originally sourced by Andy Anderson. Issa Tseng, the author of

apollo13realtime.org helped me reflect on the events of the actual oxygen tank explosion. Her website also offers a unique source to the work in Mission Control at the time, with the transcription available there. Space historian and editor David Harland provided me with insight into the Apollo Guidance Computer and assisted in accessing some hard to find sources. Mike Jetzer of

heroicrelics.org provided me with high resolution scans of the Command Module control panels to use in the Journal. He also gave me some valuable insight into the Saturn V booster. Frank O'Brien, the world's preeminent Apollo Guidance Computer expert and Apollo Flight Journal editor, assisted me in getting many things about the guidance system right, and helped me to reflect in the most obscure technical things. Scott Schneeweiss of

spaceholic.com provided me with information about the Environmental Control System and the LM umbilical. Steve Jurvetson gave me the permission to use

unique photographs of Apollo artefacts from his collection . Apollo 13 EECOM

Sy Liebergot provided me with photographs and interesting correspondence. Encouragement, comments and feedback have also come from

Ben Feist , Stephen Slater, Ken McTaggart, Robin Wheeler,

Emily Carney , Ron Burkey of

VirtualAGC, Charles Fishman, Wes Oleszewski, James Oberg, Stephen J. Garber of

NASA History Office , Andy (the engineer dude - you know who you are!), David Charney, Jeremy Cooper, the curatorial staff at the

Kansas Cosmosphere , Stephen Slater,

Dwight Steven-Boniecki , Jim LeBlanc,

Simon Plumpton - just to name a few. Many others have provided commentary, encouragement and critique, which has been of great value.

Special thanks go to my family and friends who have supported me throughout the making of this Journal, and in everything else I have done in life. This could not have happened without you! I also want to extended my best regards to editor, author and friend Tuomas Marjamäki of

Docendo Publishing , who was the first to hear about this and told me to go for it. I also have to thank Larry Nemececk, for giving me the first push on the road that led here, and Dr. Kenneth Hayashida, for the next one.

Boundless thanks go to the steely-eyed missile man that is David Woods, whose passionate scholarship has fueled my own interest in space travel for the better part of my life. Giving me the chance to work on AFJ has been a life-changing event which I expect to have immense repercussions for years to come. My full hearted thanks go to him for his support, assistance and his warmth. Cheers!

Johannes Kemppanen, writing for the AFJ team, 2020