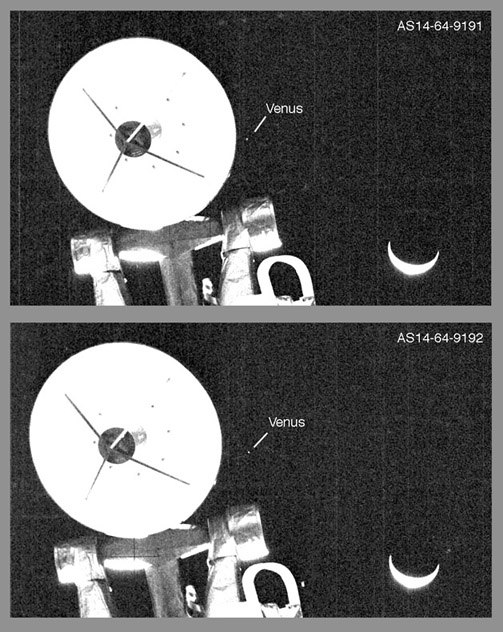

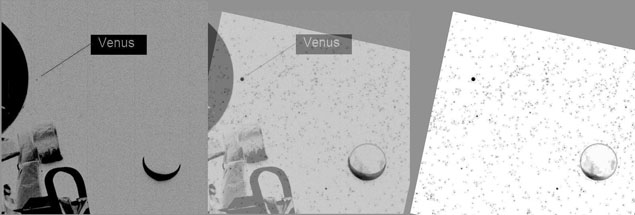

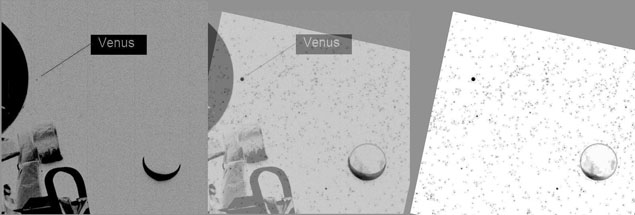

This comparison has a negative (reverse) detail from AS14-64-9191

on the right and a negative detail of Venus and the Earth from Starry

Night. The latter has been rotated and scaled to match the

mission photo. An overlay of the two images is shown at the

center. Note that we are able to match both the separation

between Venus and the Earth and the Earth's size, which further

confirms that the star-like object is Venus.

Even though Venus's angular diameter as

seen from the Moon was only 21 arc seconds - about 1/325th of Earth's

- it has the same surface brightness it would have if we were

right on top of it, because of the inverse square law of light

propagation. Because Venus is covered with clouds, and closer to the

Sun, its surface brightness is roughly twice that of Earth.

Consequently, an exposure that gets the Earth right, will also

necessarily show Venus. This is why you can see Venus in broad daylight

if you know exactly where to look - and can manage the trick of

focusing at infinity when confronted with an otherwise featureless

scene.

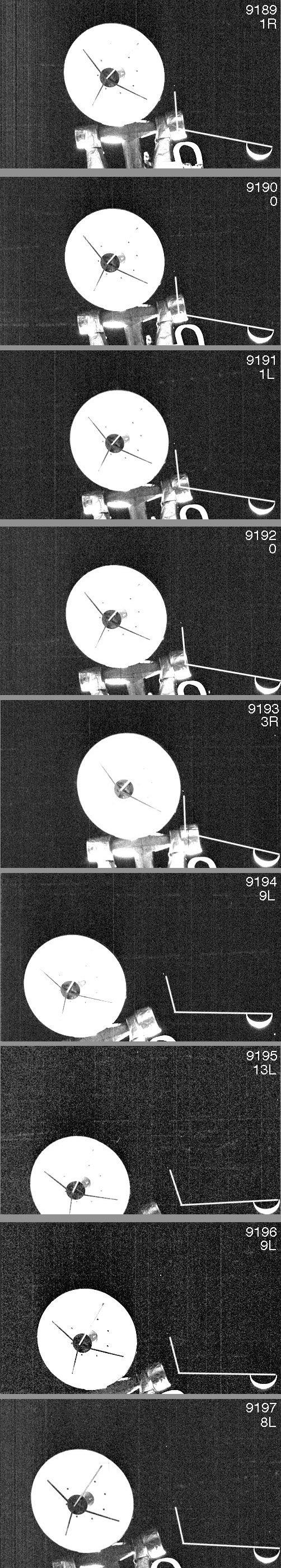

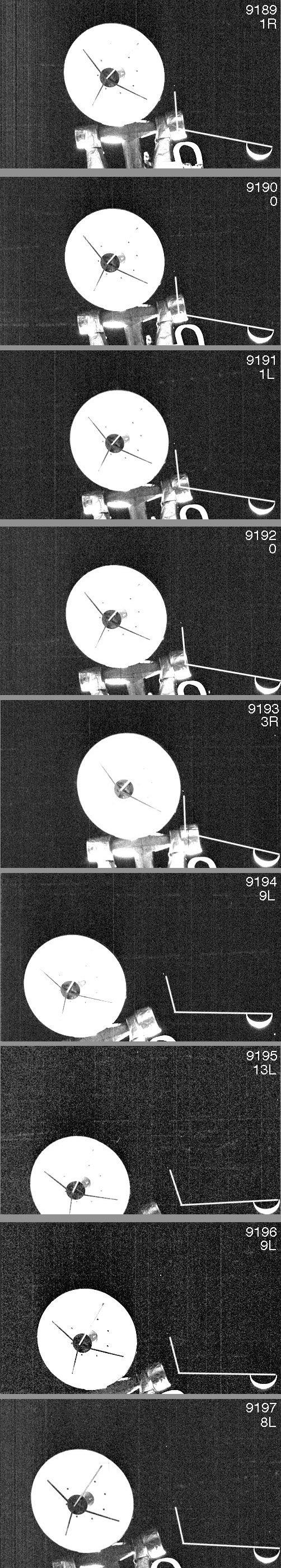

As mentioned above, Venus is

present in all nine of the images in Al Shepard's sequence of Earth

photos. In many of the images, we can also see bright spots

which, because they don't repeat from frame to frame, are undoubtedly

due to dust on the film or on the scanner, or some other cause

unrelated to what was actually in the sky over Fra Mauro. In the

following film strip, the details from the mission photos are presented

at the same scale and with the same brightness enhancement (255 levels

reduced to 50). For ease of comparison, an L-shaped figure was

drawn from the detail of AS14-64-9192 with the longer line connecting

the horns of the crescent Earth and the shorter line pointing at

Venus. The L-shaped figure was then superimposed on each of the

other frame details after a rotation needed to put the figure into same

orientation relative to the crescent and to Venus. No scaling was

done. Rotation of the L-shaped figure is necessary because

Shepard took the photos while holding onto the LM ladder, leaning back,

and holding the camera in his hand. As can be seen in the film

strip, he was in much the same position while taking each of the first

five photos but then leaned to his right - moving Venus away from the

rendezvous radar antenna - for the last four photos. Possibly he

saw Venus and shifted to his right to ensure that he captured it in at

least the last four images. We don't

know if he changed f-stops, but all the frames were undoubtedly taken

at 1/250th of a second.

Animated gif by Yuri Krasilnikov,

after a similar animation posted

at ApolloHoax.net

by 'Data Cable'.

Details from the nine frames taken by Al Shepard at about 1207

GMT/UT on 6 February 1971. The L-shaped figure was constructed as

an overlay to 9192 with the long line connecting the horns of the

crescent Earth and the short line pointing at Venus. The L-shaped

figure was then superimposed on the details from the other frames after

a rotation to reproduce the positon of the figure relative to the

crescent Earth and Venus. No scaling was done. Note the

various star-like spots, particularly in the later frames.